1. BRUH, WTF IS SCHATTENFROH?

One calls this a review.

I’ll explain this as clearly as possible: Nobody is imprisoned. Nobody seen somebody was writing 666 all over Berlin. He pulled up to 666 Earth-as-draft Avenue and now he’s trapped in the middle 6. Schattenfroh was writing the numbers. Schattenfroh is his jailer. Schattenfroh is making him write a book.

But he ain’t got no paper, no nothing, he’s writing with his brainfluid,

My memory drips. I wonder whether it’s ever dripped itself dry. Whether this writing, which here takes place with an invisible pen, succeeded in one day transferring over my soul, whether my memory is thus empty.

The book he’s writing is called Schattenfroh.

It’s a book with a simple mission,

Society demands amusement. My mission is to write everything down from the beginning. I said it can’t be done. I don’t know when the beginning is and I don’t know what everything is.

We do have to endure some cyberpunk kookiness at the beginning of this book.

Kudos if that’s a boon to you, if you’re like me it ain’t, but endure the brief snag: all the whirrings, buzzings, brainfluid, prisoncells, headsets, wires, equipment, mysterious jailers, function to set our Nobody in a barren Patmos, in the bereft landscapes of Beckett, here is a 21st Century Apocalypse in the greek sense of the word: this is a vision, a revelation.

Nobody sits on the upper crust of the wreckage of literature, history, society, culture.

He is Bach playing a requiem for our civilization.

Nobody is everybody, especially all the heretics, martyrs, mystics, and sufferers.

Human society is a story of pain, we’re not Christ in his glorious resurrection, we’re Him while he suffers on the cross,

The entire body riddled with splinters of thorns, flagellation-wounds everywhere, split and torn skin, holes, tears, hematoma. The hands are twisted, the fingers curled up like claws. The blood spurts from the page and blood runs from forehead and temples.

Because unfortunately,

The world is a wicked inn. Sin dwells in the body, here it swarms with the naked, the impaled, those given over to the game, cuckstool-demons and fire and birds flutter forth from the ass. Deception rules everywhere. Music is the work of Satan.

Is it all death, taxes, rot, ruin?

Possibly, but as Nobody tells us,

Only if the preservation of the corpse of a society is no longer worth it does art end.

Schattenfroh believes in the preservation of society’s corpse.

This is not the end of art.

The book don’t call itself a novel, it calls itself A Requiem.

A requiem is a mass for a dead person in the Catholic church; there is a black gravity, a pall over that word, but what we forget is that the form of the requiem believes in the resurrection, so it is a prelude to triumph, return.

Schattenfroh the book does not believe in the resurrection. That is one of the minor heresies in this extravagantly heretical book.

We are like Jesus’s mother,

who must’ve recognized her son in the same moment she saw the crucified Christ whose death she blames herself for in perpetuity, a death that, at the same time, makes her very proud. Her sorrow shall never come to an end, resurrection is not an option for her. From now on, she shall carry her son around her neck as a gold chain with a crucifix dangling from it, a crucified man who is permanently hanged.

There might not be resurrection, but there is continuance, endurance after death.

We might stick around like Nobody, dripping our memories dry, romping around in Bosch paintings, getting crucified, getting burned, being bored to death by a lecture on how Gutenberg's printing press works, getting a lecture on architecture, being put on trial for smuggling a map, laying eyes on the gouty grotesque Charles V, reading thru our Father’s library in a vast empty room, getting eye-boners (literally), looking at pictures of Mommy and Daddy (unconnected to the eye-boners, thankfully), walking thru our childhood home, watching lurid videos on the train, witnessing Mommy and Daddy age and die, incessantly making anagrams, wondering where Schattenfroh is, realizing Schattenfroh is right there, drinking at a pub with your brother, pissing your pants (if you had pants), etc., etc.

Everything I mentioned happens in this book and it’s not nearly an exhaustive list.

There’s intentionally 1001 pages, and the book is like the 1001 nights, it’s story after story after story. Some, sure, are grim and nightmarish, but this book is consistently funny and exquisitely playful.

Here’s one of my marginal LOLs chosen at random: Nobody is talking about an ostensible shadow-self (schatten!) that we find out later on is his brother,

He has been with me since my childhood. As far as I can recall, it began with a pair of pants made of coarse fabric, my mother found them to be cute on me, they hung loosely about my knees and were just a bit too long, I would grow into them Mother said, but there was no way I would ever like the pants, they were unbearably itchy, I refused to put them on, for which reason my mother refused to love me, thus did I have to choose between love and itching, but opted for a third thing, which I called he, he had to put on the pants, while I myself decided on red wide-wale-corduroy pants, which my mother, as she said, ‘couldn’t see on me’

The specificity, the cattiness, the fact that his Mother doesn’t love him over a pair of pants!

Ok, here’s another passage; the metaphor of literature as eating:

But a lot of Thomas Mann necessarily means a lot of bowel movements, Father didn’t think of installing a toilet down here. For me, Schattenfroh acts as a toilet-paper dispenser, thus do I shit into my own book. And, in miraculous fashion, the blank pages absorb the smell, while, simultaneously, the digested Thomas Mann makes the white script legible, for, when I unroll the digested Thomas-Mann Turd from one page and onto the next, I can read from this version of my book most merrily

Schattenfroh swims happily in that ludic sea of literature (of which Tristram Shandy is an enormous touchstone) that vaunts literature as simultaneously the most important thing in the world and derides it as meaningless frivolity:

—//THIS//is//SHIT//—

Schattenfroh is literature for the 21st Century.

A century that might seem a Gehenna because of the geological layers of history and destruction that we live atop and build upon.

But if it is Hell, it’s our Hell. The only one we got.

That might be Michael Lentz’s most heretical position in this book: We live in a painful deathbound nightmare, but there’s still time for joy, play, amusement, and yeah I’ll say it, erudition.

Are you fuckers scared of a learnéd book?

Some numbnuts in the LA Times was deriding big erudite books with long sentences as a fetishized genre called brodernism.

To me that’s the kinda energy that led to the NCAA banning dunks cause Lew Alcindor was humiliating all the white boys. I mean shit, are we pissed off when Wilt Chamberlain scores 100 points? When Kobe gets 81?

Shouldn’t modern players be trying their best to surmount the past? Shouldn’t we be attempting things in literature never attempted in prose or rhyme?

Or nah bro, if you’re cool I’m cool, you know, maybe you’re content with the rotten turnips and jellybeans they’re feeding you and calling it sustenance; here’s our provocative Nobody throwing down the gauntlet,

Here, for example, in the contemporary literature section, which in comparison with the other sections, stands out by way of its unquestionably beautiful books, we have colorful and layered compositions, coated with rolled fondant and crowned with flowers from the piping bag… The art of baking makes these round loaves of bread superior to any content. They make one hungry for more and do not sate. If one eats five of them in a row, one thinks oneself to have perceived a certain nullity in them.

Maybe the United States is content to have abdicated its agon with greatness. Maybe we feel like society is a corpse no longer worth preserving.

That’s not the way I feel.

I think the English translation of Schattenfroh by Max Lawton, —the most ambitious of these socalled brodernist works, a book which sits easily on the top shelf of books published this century, —is a challenge to invigorate the American novel.

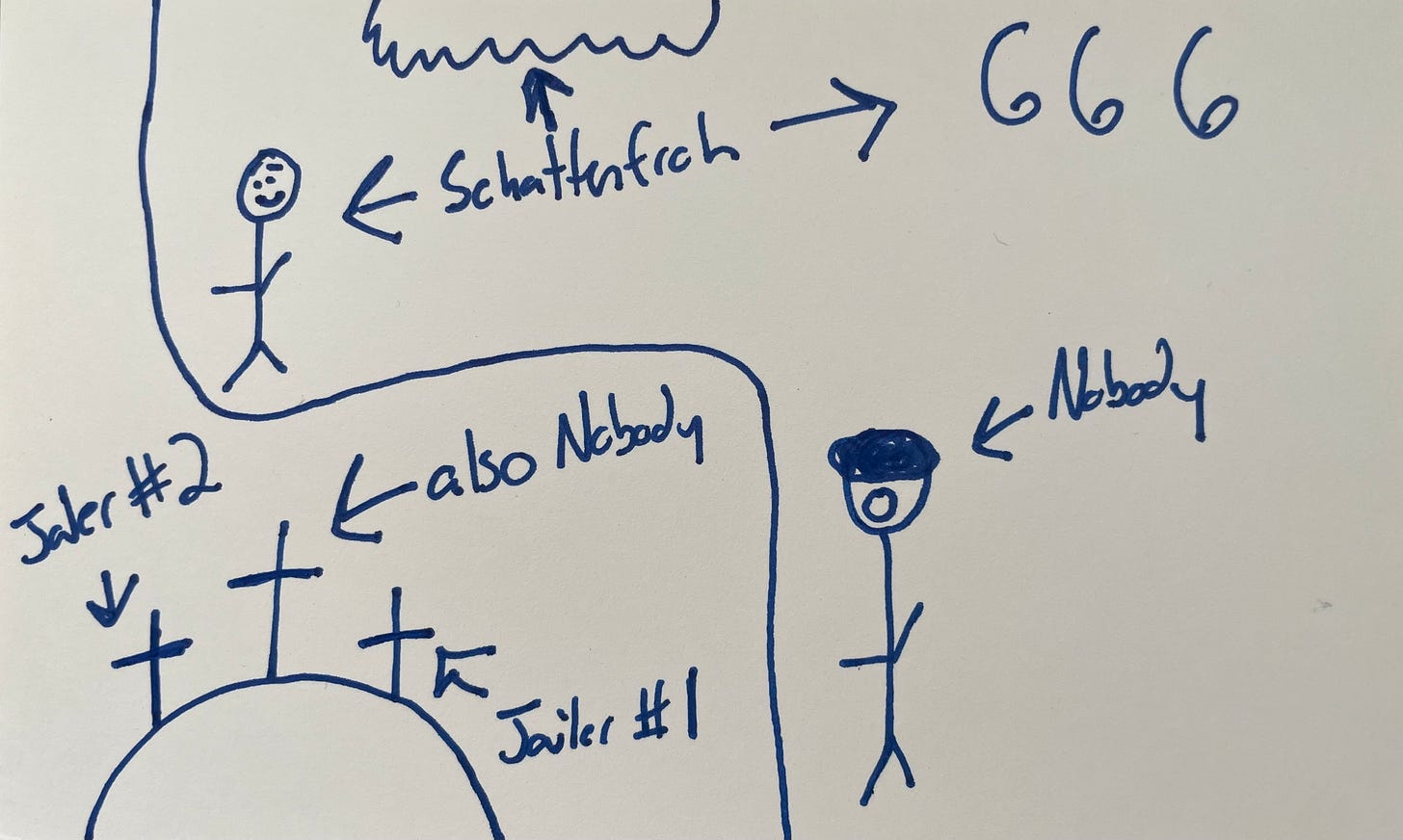

Oh shit, also, I drew this helpful diagram for you to easierly envision what’s going on spatially in Nobody’s cell,

2. FREIHEIT!

One must understand that history is not as clean as geology.

Darwin, an irrepressibly geological thinker, lays out the endurance (never progress) of the natural world in layers,

As buds give rise by growth to fresh buds, and these, if vigorous branch out and overtop on all sides many a feebler branch, so by generation I believe it has been with the great Tree of Life, which fills with its dead and broken branches the crust of the earth, and covers the surface with its ever-branching and beautiful ramifications.

One would think we could slice time and look at the layer cake of history, years piled on the harms. But the engine of the natural world strives for commonality, snuffing out monstrosities and aberrations, eliminating their generations.

But in history, the sui generis reverberate, they ripple and ripple in our pond.

Schattenfroh is keen about history.

Nobody is physically trapped in the historogeological record, he’s as much in 2014 as he is in 1525.

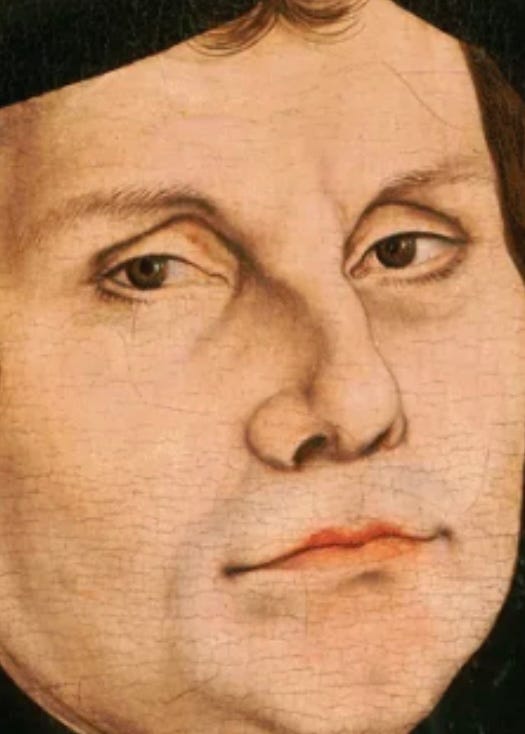

His jailer is as much the technofascist Schattenfroh as it is Martin Luther with his vicegripinfluence on the German language.

Martin Luther is really important to Schattenfroh. Especially in his malignant dichotomy with Thomas Müntzer.

Thomas Müntzer is mentioned early on in a goofyserious passage when Nobody is chatting with Knecht Ruprecht, a companion of St. Nicholas in German folklore,

I remind Knecht Ruprecht of the martyred Santa Claus of December 23rd, 1951, who was publicly hanged and burned in the name of the Church in the forecourt of Duria Cathedral before the children who believed in him. I warn this Knecht that precisely the same could happen to him, as he too is a heathen, a heretic. Ruprecht also recalls this incident, he reminds me of the fact that Santa Claus rose again and thus shall it come to pass with him, should he also be hanged and burned. I am actually and always Thomas Müntzer, Ruprecht says.

(This whole martyring Santa Claus business is from an essay by Claude Lévi-Strauss which I don’t really know nothing about.)

It’s also an important reference because Martin Luther, being the popularizer of the Christmas tree (yes!) is a Father Christmas of his own, and in this passage, he burns, and Thomas Müntzer survives.

Ok, I thought all this LutherMüntzer shit I’m gonna tell you about was sick as fuck and I was really obsessed.

And that’s one of the pleasures of a such a knowledgegravid book: it can send you out spiraling (but it don’t have to! hold that thought!).

Martin Luther (1483-1546) and Thomas Müntzer (1489-1525) were rabblerousing contemporaries.

Both of them were born in small mining towns; Müntzer was the son of a mine worker, and Luther was the mine owner’s son, —a distinction that would define their differences later on.

Luther revolutionized Europe with his 95 Theses in 1517 and his New Testament translation in 1522. He also had a bigtime pamphlet in 1521 called “On Christian Freedom” and the cover of the published work had the all caps word FREEDOM emblazoned on it.

Luther got Thomas Müntzer a job early on in his career, but they became bitter rivals, especially over that question of FREIHEIT (the word freedom appears at least a couple times in the book in all caps, Michael Lentz is encyclopedic in what he knows about German culture and history, so I’m sure it is a reference to Luther’s pamphlet).

For all of Luther’s poperebuking surliness, he believed in earthly Law and in temporal political power.

Thomas Müntzer was an apocalyptic heretic in the spirit of Jesus Christ.

He’d go from town to town setting up his congregation and preaching to the regular folk until they were in such a fervor that Müntzer had to sometimes flee in the middle of the night to avoid death at the hands of Them-in-charge.

Get a load of Müntzer’s style from his Prague Manifesto (quotations from which I am sure are embedded in Schattenfroh but I don’t know where),

I state freely and briskly that I have not heard one donkey-farting doctor whisper the least fraction or trace of the order of God and all creatures, let alone proclaim it out loud. Even the most illustrious Christians (by which I mean the priests who are firmly rooted in Hell) have never once had an inkling of the whole and undivided perfection of it all.

His main contention was that you can have an unmediated experience with God thru the Holy Spirit without any fucking books or priests or laws. What was important to him was private revelation.

Schattenfroh is a book about private revelation in the form of a private revelation.

I’m being Mr. Bookman, going outside the book, paying attention to the 183 or so books cited in the bibliography in the center of Schattenfroh (which is a fucking sick reading list), but you ain’t need to do that and I think Schattenfroh itself lowkey derides that type of reading.

The Bookmans are being Luther, when the real geisthero is Müntzer.

STOP LISTENING TO ME FUCKERS!

LET THE HOLY SPIRIT GUIDE YOU!

YOU DON’T NEED NOTHING ELSE!

THE SECRETS ARE IN THE WORDS!

What happened to Müntzer? The heretic that outhereticked Luther?

He rabbled his rouses roused the rabble of peasants filled with the spirit and they charged Frankenhausen and in a few minutes peasant blood soaked the hillside.

Müntzer fled and was captured, tortured, and killed on May 27th, 1525 (my mother and Céline’s birthday, different years of course; this year is the quincentenary).

Müntzer’s holy head was displayed on the city wall for years to come.

(Scroll past these parentheses if you’d like and continue with the LutherMüntzer, but here’s Schattenfroh on the idea of the city wall,

The city wall, he says, is the desperate attempt to vanquish beauty as a fleeting form and appearance and to enable persistence in those same forms, a city wall as a temporary means of preservation and healing, and that, he says, makes it vulnerable, the external enemy is often indistinguishable from the internal, the enemy, incited to jealousy, would like to tear down beauty, thus does he make a run against the wall and thus are there always two forces at work, the will to beauty and the will to ugliness, he who creates wants eternity, which, however, as it no longer makes any difference, is meaningless and soon comes to appear as ugly in its ossification, thus must the eternally creating also be the eternally destroying—that which brings about new meaning.

The above quoted sparks a feeling I don’t often get when reading contemporary fiction: What a fucking crazy sentence!

Here’s Schattenfroh talking about its own flow in the guise of talking about the novel Michael Kohlhaas (1810) which has its own agon with Luther and which according to Nobody has “the most beautiful prose in the German language”,

the sequence of sentences, the alternation of short and long ones as the sequentiality that characterizes human affairs, of events and the reactions to them, is the smoldering, surging, raging, calming oneself anew, accumulating, diverting, refusing, devouring, flayed, torn body, in which everything is bundled up, the body that attracts everything, then hurls everything away from itself, an uproar-poetic of the inner current that causes the body to twitch through the country and the twitch is the pen against paper, shorthand of the mind and psychography.

End parentheses.)

Martin Luther is responsible for the death of Thomas Müntzer.

He appealed to Them-in-charge to stomp out the peasants like vile swine because, as Schattenfroh opines on a brilliant 8-page essay on the commandment Thou Shalt Not Kill late in the book,

Luther was lucky not to have died as a heretic. In Thomas Müntzer, who had so vehemently renounced him, he saw the Anti-Luther whom he had to suppress within himself. The Anti-Luther was thus to die in his stead. If Luther had been taken at his own word—i.e. against Müntzer—he would have had to have been executed.

Luther annihilated the most extreme and powerful manifestations of his ideas, aconchegated1 himself to the monolith, became like the limpid Christless cross hanging on a heathen girl’s fine neck, like Jesus reunited with God the Father, he became Schattenfroh.

3. THE HOAX AS FORM

One must understand that art is an eternally arcane theology.

The true artist should be indistinguishable from a heretic.

The heretic is enflamed by personal revelation; so all-consumed by ardor, he enflames others in an unstately, unpalatable way.

Nobody is a heretic. To the dismay of Schattenfroh the Jailer, he’s,

writing a heretical book that strives to look into the future as only God can do, for this act belittles the present as set against the future by inventing even more devastating annihilations… the book insults the city and the father and brings them into disrepute; and that all of this heretical, future-assuming, present-reducing, doom-inventing, and home- and origin-abusing claptrap is recorded in such minute detail is the greatest sacrilege of all.

Nobody’s apocalypse-inducing Schattenfroh is demonically legion,

Here, you see your book in about one hundred different versions. Each version differs from every other version. If we can’t get rid of this bad habit of yours—your perpetual lying, then selling these lies as books—even if this habit can’t be entirely done away with, one can, at the very least, improve upon your lies and isn’t it wonderful to imagine that everyone shall be reading a different Schattenfroh?

Schattenfroh is a holy lie; nobody understood art as a holy lie better than the Medievals.

A culture without the printing press, that gotta copy out every book by hand, with all the emendations, accidental and intentional, germane to that process, has a different attitude toward The Book.

Every book is a personal revelation. God is loud.

The printing press, and the exponentially image-doused world we live in as the natural acceleration since Gutenberg, create a condition wherein personal revelation has never been more possible, or less likely.

Schattenfroh knows that Schattenfroh becomes Schattenfroh thru mass production. God is still there, but he’s whispering.

This book is obsessed with the book as object, —the most important object of all time, one could argue. We get a hilariously boring, descriptively excellent lecture on the early printing process.

Nobody witnesses his book being typeset and printed,

Newly printed sheets of Schattenfroh, the papers look like a cauldron of bats sleeping upside down, but devil knows what this page here is:

The page in question is from Part 2 Chapter 24 of Don Quixote printed in Spanish on the next page.

Nobody’s asked,

Did you write that?

No.

How did that page get in there? It might lead one to conclude,

That I myself do not run the regime that rules over my book, but only open and close the inflow-channels without having any influence on the overall flow

The Holy Spirit is guiding his hand: Schattenfroh is an act of psychography.

Here’s how that passage of Don Quixote opens,

The man who translated this great history from the original composed by its first author, Cide Hamete Benegeli says

Cervantes is a trickster, hoaxster. He got a medieval mind.

He says he found Don Quixote written in Arabic and then paid someone at the market to translate it, and now he’s reaping the profits.

He’s not unlike his 13th Century coterrainian (another huge influence on Schattenfroh), Moses de Léon.

Moses de Léon was a Rabbi who found an ancient manuscript by the 2nd century Rabbi Shimon ben Yochai revealing the secret truths hiding in the bible and he copied it down and published it.

Except no he didn’t.

He wrote the whole thing himself in a simple, strange Aramaic, a contrived idiolect he believed got him closer to the mysteries of the universe.

The Zohar became the most important text in Kabbalah (Jewish mysticism, which I don’t know much about, but which is hugely present all over Schattenfroh).

Here’s a passage from the Zohar,

When the moon was conjoined with the sun, she was luminous, but when she went apart from the sun and was given governance of her own hosts, her status and her light were reduced, and shell after shell was fashioned for investing the brain, and all was for its good.

Reading the Zohar, you get the simultaneous feeling you’re being duped but that enlightenment is just around the corner, you just have to keep digging through corridors of shells.

People started to become suspicious of the Zohar’s provenance because after Moses died, someone went to his house trying to buy the ancient manuscript from his widow, and she said there wasn’t ever no manuscript.

Imagine being Mrs. de Léon. Your husband spends all this time on this big goofy book that don’t make any sense and then he croaks leaving your ass broke with kids to feed and then you can’t even sell his ancient old manuscript cause it don’t exist!

One can imagine her shaking her fist to the heavens, MOSES!

Here’s Nobody on the train in a very contemporary scene, after watching violent videos on his cellphone,

Then my battery runs out. My disappointment at this causes me to get a bit irritated, however, the prospect of eventually continuing consoles me immediately… I would like to see it very precisely, each detail, the face contorted in pain, the exertion of the killer who doesn’t wish to show any weakness, just as it was in the Middle Ages, so is it also now. The problem is that we’re dissatisfied with the quality of the images. Is there an innocence of the senses? It is only beautiful if it is not true.

It is only beautiful if it is not true.

This book is obsessed with the falsest holiest image of all time: the Shroud of Turin.

The Shroud of Turin might be the burial cloth of Jesus; it’s a 14 foot linen cloth embedded with the shadow (schatten!) of a dead man with crucifixion wounds; it’s been carbon dated to around the 13th century, but we’re not sure how exactly how the image was made, and there’s real blood in the cloth.

One can imagine what those glorious hucksters were thinking when they made it,

Why this legibility? To arouse disgust? To sublate time and distance? To be right there, right then? The more drastic the representation of pain, the better it can be imagined, the better it can be sensuously brought to mind, the better it shall be remembered. The goal of art is compassio, taking part in and being part of the sufferings of Christ.

The Shroud of Turin is simultaneously a meaningless piece of crap and one of the most holy, important things in the whole world.

Whoever made that was doing something inordinately reckless, practicing art as sacred terrorism: an attitude one might consider modern but which we’ve lost in a prim, staid, fluent, and ornamented culture that frets about plagiarism (a stupid invention that resulted from art becoming product) and citation.

Schattenfroh is showing us that the future of art in the 21st Century is medieval.

We must copy down the old books by hand, changing what needs to be changed to suit our purposes, transforming the historical into the personal into the heretical, we must listen to Thomas Müntzer and become vessels for the Holy Spirit.

Schattenfroh is also the Voynich Manuscript.

The Voynich Manuscript is the Kookiest Book Of All Time. It’s a 15th century manuscript written in a language nobody can decipher illuminated with crazy depictions of plants and weird machines and like sometimes naked people.

Nobody has ever figured it out! They don’t know what it’s for, they don’t know what it means, or why it exists. It might’ve just been a fucking prank.

That’s that Schattenfroh energy though: either this contains all the mysteries of the universe, or it’s a goofy-ass prank, or shit, it might plausibly be both.

Ok, now I’ll talk about Finnegans Wake so please scroll by.

It’s impossible not to compare a book this Sterne, medieval, oneiric, shifty, and drenched in cultural particulars to FW: the image for that book within that book is an illegible piece of crumpled paper found atop a pile of rubbish by a hen, —I think Schattenfroh would happily be pecked by that hen.

Schattenfroh starts and ends with the same phrase. And the central characters are constantly changing up and becoming different people and archetypes.

But Schattenfroh is significantly easier to read. There’s not much word and sentence level confusion.

I think it’s because Schattenfroh is a Book for the Eye and FW is a Book for the Ear. Joyce is agoning with Shakespeare and the book, despite its visual games, is preached out to the groundlings like a radio broadcast.

The medium Schattenfroh is interpolating into its form is of course the internet. We are an eye-shackled culture.

(Curiously, there’s no Joyce in Schattenfroh’s bibliography. And I think that’s important to understanding the style of this book.

As I’m sure you’ve noticed, Schattenfroh is full of writing of tremendous beauty, but the beauty is never blazing like Joyce’s, it’s frigid, like the late Beckett.

We’ve replaced Joyce’s orgasmic “Yes” with a robust “OK”. )

Why read a book that you can’t totally understand?

Like Gershom Scholem tells us in his introduction to the Zohar,

the conclusion which has since the earliest of times been drawn in the recognition of a sacred text, namely, that the effect upon the soul of such a work is in the end not at all dependent upon its being understood.

You don’t gotta understand Schattenfroh. Just submit to the possibility of a secret mystery.

4. OH YEAH, I FORGOT: THIS BOOK IS AUTOFICTION

One must understand that the life of a heretic leaves little room for love.

(There’s no Love in this book.

And if I had any quibble, —and I believe a book this ambitious, fascinating, and fun is beyond reproach, —it would be that as a reader, I like a little romance, a little sexual energy, and this book is devoid of Love in any guise.

Very intentionally so, it’s a sexless masculine landscape like Beckett’s, and it’s tied to a denial of the Resurrection, —Jesus is always the Crucified One in this book, never the Redeemer, —Love and Salvation are not operative principals, They endured, one could say, I can’t go on. I’ll go on.

Acceptance and endurance are kinds of transcendence.)

The first rung of heretic-suppression is the family. Schattenfroh, for all of its other punning connotations is a family name.

You’re born into Schattenfroh’s carethrall,

Is family the fundamental evil of the world, out of which the world of all evils emerges?

I’m sure Lentz knows very well what Vico tells us,

families can only have taken their name from the family servants, famuli, belonging to the fathers in the state of nature.

You must belong to your Father in his manifestations as Daddy, as God, as State. Furtive budding individuality of any sort is mutiny: a monstrosity that is bad for the continuance of the contiguous organism, and it must be eliminated,

Father is a secret made flesh, I never knew exactly where he was coming from when he got home, he slammed the garage door, strode into the house, couldn’t be found for a few minutes, then was suddenly standing there and saying that Mother had complained about me and, as Mother had complained about me, he would have to hit me a little bit with the cane so that Mother would feel a bit better. Recently, I had taken to using words that Mother didn’t know, a family depends on common understanding, he said, as such I should not use these words anymore, what kind of words do you mean, I didn’t know what the words in question were and simply said certain terms that I’d read without understanding them, metaphor, for example, or dissociation, and Father’s cane made it clear to me that he knew very well what these words meant, no more of these words will come to you, right, not after I’ve used pain to get them out of you.

Father is also God and Nobody is also Jesus. Nobody is trying to understand the crucifixion as a son.

What kind of father would put his son thru that? Such an extravagant torment that he would be shouting from the cross, Why have you forsaken me?

(And that heresy is vital to understanding Nobody as a character: the Son is not the Father. But he suffers for his Father’s designs.)

Mother, of course is also Mother Mary, but unlike the acquiescent Virgin (who is no mother but only stands for the institution of the mother), she’s not interested in this role thrust upon her,

She asks herself, for example, why she should give birth to a son who shall grow further and further apart from her and whom she shall never understand, then, later, she asks herself why she gave birth to a son who shall never be grateful.

(Is it any wonder why Nobody don’t got a girlfriend?)

Mother was more comfortable in the role of Daughter,

Mother, who loved her father more than anything, who clung to him like nobody else—this despite her yearning for freedom—and cared for him as he was wasting away with lung cancer, right up until his death, in such a way that the idea of one day dying of cancer nested away inside of her.

Family is a constant misunderstanding,

For his whole life, he failed to get to know his children. For his whole life, his children have sought to get to know their father.

Now Nobody is left bereft, both his parents are dead, and,

That’s the saddest thing of all, to have no more mother or father to tell one what one can and should do.

Now all he can do is drip his memories dry and look at photographs, trying to understand them as people, trying to understand why there was all that pain, strife, misunderstanding.

Couldn’t it have been different?

in my father’s hidden library where one can find photo albums that we never came across as children, the photographs showed vulnerable people, shy and in need of help, before they became dashing and sublimely superior to their own childhoods once more, our parents didn’t want to show us this—that they had been just as small and dependant as their own children, who had no notion of this, if the children were to have seen the faces of Father and Mother, their submissive posture, wouldn’t they from then on have opined that they were dealing with their own kind and wouldn’t the parents’ authority thus have been destroyed?

Nobody longs to see his parents as more than looming brooding archetypes of control, an impulse that is passed down generationally,

Does Father wish to see a milder image of his father than the one that he himself holds in his memory? Can Grandpa really have been more warm-hearted than Father, who isn’t warm-hearted at all? Did [the town of] Prüm contribute to the cross-generational unyieldingness that caused Father to grow up with no empathy at all? No farewell-embrace, no gazing back. One goes for a stroll on Sunday with the kids. On weekday evenings one interrogates them to determine whether they’ve been a burden to their mother. They are ever a burden to the mother, for the father is never around.

Grandpa was locked up by the Gestapo for three months in a madness-inducing solitary confinement. A situation extremely similar to the one Nobody is in: he’s trapped relieving the history of his family, his city, his culture.

Cycles persist in perpetuity,

In some families, family is the only subject, generations spin round in a narcissistic circle, the female or male line is a single person who is reborn in their offspring and only dies when nobody else follows.

Nobody’s landscape is antithetical to reproduction. Nobody is floating in eternity, temporal generational continuance ain’t relevant.

Plus, the cycle must end.

Nobody takes his name from Odysseus’s pseudonym when he’s duping the Cyclops which is extremely relevant because our Nobody is also on a homecoming mission.

Michael Lentz is from Düren.

(Yeah Schattenfroh is about Michael Lentz believe it or not.

His parents are dead. I bet his dad died on August 20, 2014, the date named in this book.

Schattenfroh is radical autofiction. As it must be because that is the only relevant form for the 21st Century novel.

The subject of the 21st Century is ME.

The future of the novel is thru ME.

Not away from ME.

Aesop is dead. We must stop fabulating.)

Düren endured the deadliest European bombing in World War 2.

Fifty pages into Schattenfroh we get an almost 100 page handwritten list of names of all the people who died in that bombing.

It’s a brilliant move formally because it chugs us along this big book undeservedly and we feel like we’ve made serious progress; but also because it shows intimately how this book sits atop history’s rubble. Lentz takes that rubble very personally.

But why all this looking back at ruins?

Is the destruction of the beautiful not its consummation? The ruin is the pinnacle of the beautiful, the threshold of the is-and-is-not A ruin is, is not. But must it first have become a ruin over the course of centuries, during which nature found it mete to, for example, burst through Rome’s Stoneworks of Eternity, then to dissolve what was structured as an eternal order into its constituent parts, passing over any threat from Rome that nature too would be brought under its control? …If ruins are script whose sentences history reads, then it is so that the blowing-up of a ruin is the yearning to erase this script so as to set another in its place, but the sentence ‘campus ubi Palmyra fuit’ cannot be exploded; by lying atop Troy, it regains the consolation of eternity through the metascript of the explosion.

(Of course the reference to explosion of the ruins of Palmyra is about the destruction caused by the Syrian Civil War, another reminder of just how 21st Century Michael Lentz’s concerns really are.)

Schattenfroh is a ruined book of the dead.

But while we’re alive, we can’t just let the dead flit away from us; here’s Nobody looking at a picture of his mother as a little kid, remembering her childhood nickname Stintelein,

Stintelein is not kitsch. I do not pray to the photo, do not fall to my knees before it, do not mistake it for a statue, it ought not to bring me any consolation either, indeed, I know that Mother shall not come back to life by way of me worshipping the image, she returns dead, she shall only be dead forever for as long as I live. Mother’s world has no soul, but it makes the world more consummate, it represents the Manes, the departed spirits of the dead. If I lose it, I’ve lost Mother for good. I shall keep and cherish it so that the spirits don’t stalk me in my dreams or send sickness and death.

Earlier in the book Nobody tells us that the purpose of literature is to remember the dead. Maybe that’s right.

To remember and accept,

This strange life freezes like a candle. Nobody wants it, life, everyone accepts it, only those who exercise violence do not accept it.

And once we can accept the parameters of this possible-Gehenna, we can bask and play within the bounds.

That’s part of Literature’s essential role,

Literature is no dalliance, no pastime, it is time. Life has no more intense experience to offer, life is truly and only there to be read. One reads life away, letters are merely another sort of spectacles, which allow us to see things that life conceals with its own things.

The publication of the English translation of Schattenfroh is a sign that Literature is still alive, vigorous, and necessary.

READ IT, FUCKERS!

One calls this a review.

Check out the first ever review of this book in English by The Untranslated, —he got the Schattenfrohball rolling.

From the portuguese aconchegar: to get close to someone, especially for protection.

Aconchegated!

A lot of things you said about the book made me think of the Argentinian Daniel Guebel’s El Absoluto, especially “That’s that Schattenfroh energy though: either this contains all the mysteries of the universe, or it’s a goofy-ass prank, or shit, it might plausibly be both.”

“autofiction … is the only relevant form for the 21st Century novel.

The subject of the 21st Century is ME.

The future of the novel is thru ME.

Not away from ME.

Aesop is dead. We must stop fabulating.”

This is a thought that I think everyone has had or will have and that is spoken in your voice—it refers me to Emerson’s “Self-Reliance”: “To believe your own thought, to believe that what is true for you in your private heart is true for all men,— that is genius. … In every work of genius we recognize our own rejected thoughts; they come back to us with a certain alienated majesty.” Maybe our own rejected thoughts, because we rejected them and didn’t say them, infuriate us. So calumny is an excellent form of praise.