VOVÔ'S ASHES

GRANDPA HUGO (1 SEPT 1942 - 13 JAN 2020)

(1) — U EVER DUMP A BODY. . .?

APPARENTLY: YOU’RE NOT allowed to scatter human ashes wherever you want.

I kept thinking, regarding our plan, as we pulled up to Engenhoca beach, in Riberia, on the Ilha do Governador (where my mom & my grandparents & their grandparents had all grown up) : imagine you’re floating on your back in the water, enjoying the Sunday carioca sunshine, and suddenly the water around you gets cloudy with what used to be my grandfather. . .

Luckily, the beach was mostly empty; few people drinking chopp in plastic chairs at the whale-themed kiosk called MOBDICK (pronouncing it in a brasilian accent adds the Y); city sanitation workers saharanly garbed in garish orange. . .

I said, “should we ask them guys for permission?” Mom said, “are you fucking crazy?!”

. . . we squealed up to the curb in our rented van; I unbuckled my grandpa & uncle’s urns from the front row; we hopped out like a bank robbery. . . squawkering=bickering about plan-details, I felt like a young parrot on a tree where all the adult-parrots are getting loudly divorced. . .

. . . we walked down to the edge of the water, plunked down the two urns, made a circle around them: mom, grandma, dad, sister, sister’s boyfriend, Gaby;

the sanitation worker put his broom down, crossed his arms, watched us keenly as a crane eyes fish-prey.

. . . our oafish trundle cultishly holding hands, enforcing sudden solemnity in what had absolutely not been solemn. . . oh it was all so funny. . . I started laughing, Gaby caught my laugh like tuberculosis, we held hands tightly to steel ourselves. . . my mom ragefully brisked thru her last words on her brother & father and stormed off, crying,

—NOBODY TAKES ANYTHING SERIOUSLY IN THIS FUCKING FAMILY!,

—MOM, WHAT AM I SUPPOSED TO DO IT’S HILARIOUS?!

—LET’S JUST GO BACK AND FORGET ABOUT ALL THIS!

—HAROLD, HERE,

my ever-pragmatic father yelled, handing me one of the urns;

he hurled the bio-degradable urn-lid into the ocean, started scattering the ashes / / would’ve been a gentle scattering if it was as easy as that word made it sound, but these ashes had been packed tight for almost six years, bunched in hard as old flour. . .

. . . my dad starts taking fistfuls of my grandpa, tossing him into Guanabara Bay like a baseball; I didn’t wanna touch the ashes at first, but once he went for it, so did I, and suddenly all this grim morbidity broke into horseplay fun as a snowball fight : —

tossing, dumping, shin-deep in the water laughing like a maniac, the wind blowing ashes back at me so by the end I was coated with a thin layer of my grandpa & uncle’s remains. . .

when it was over I took both the lidless urns out deep into the water, filled them up, pressed them into the soft sand. . . I looked to check if the sanitation worker was still peering, but he was long-gone, caught up in his own disposals. . .

. . . on the way back to the van, my mom yelled at me,

“YOU ARE NOT ALLOWED TO WRITE ABOUT THIS!”

(2) — NOT ALLOWED TO WRITE ABOUT THIS. . . ?

WHEN I WAS a kid, I was always knowing stuff I wasn’t allowed to know. . . Mom & Grandma were setting up an email address for Grandpa, pondering what the handle should be; I was 9 or 10 :

I said, “how about alcoholic123?”

I thought they would crack up; but instead, they look at me mysteriously grim, and my mother exploded, HOW DARE YOU SAY SOMETHING LIKE THAT!?

It was an extremely confusing moment for me : we all knew the truth, but for some reason, I wasn’t supposed to say anything that revealed I knew, — meanwhile I had picked up my grandpa’s drunk ass from the bathroom floor. It was no secret.

The lesson : TRUE don’t mean you’re allowed to TELL.

I WROTE A LOT about my grandpa in my first book, Tropicália (2023); — to a family-secret-spilling extent; — because I loved my grandpa dearly, and he was an excellent crux in which to explore one of my matter-most questions :

How do you love someone who is objectively bad in so many ways?

Grandpa died of cirrhosis at Miguel Couto Hospital on 13 January 2020;

his last day at home was New Year’s Day : he was fantastically lucid the night before, — even classically complaining my grandma’s rabanadas were only OK. . . ;

but he slept in worryingly late; this is what I wrote in my journal on 2 JAN 2020 :

“. . . grandma comes to me says lets see if you can get him up, I went in there he was totally unresponsive like he was sleeping real deep and couldn’t get up, not moving nothing, I was like shit, we gotta call an ambulance, my dad comes in the room sees grandpa and starts crying. . .

we waited for an hour and then they show up with the jankiest stretcher I’ve ever seen in my life. . . I had to do the paramedics job for them, get the chair down to the street get him into the ambulance, he didn’t say nothing except for a deep moan. . . we’ll see how it tuns out, very sad.”

Here is Lucia’s reflection, in Tropicália, after her Grandpa dies, thinking about how it’ll effect her young cousin Marta,

“Grandpa used to loom fearsome in our lives, so it was odd to see him blip out so puny. Marta never got to experience his raucous rage nor his nice funny turns, he was just sick: a death-ticking clock. Like a pet fish. No. Marta had already suffered so much in her nine years. . . I was worried the world’s wounds would leave her calloused and mean. That’s what happened to my grandpa.”

My grandpa was the king of bounce-back; so many times you thought he was DEAD, then he would just be FINE.

Once, we were totally sure he was brain-dead; he was a drooling incoherent shuffler, —there’s a picture of him dancing with my grandma in the kitchen: she’s moving his arms, guiding him, his head is lolling soullessly.

We thought it was the end; he had a heat stroke and we rushed him to the hospital; they found out he had some artery issue, snipped him up, and he comes back home, curmudgeonly acute like his old self, basically like, “that hospital food sucks, huh?”

We thought the same thing would happen again. He was cogent at the hospital; I had a conversation with him on January 12; I left to go back to New York; he died.

In Tropicália, I imagine a final death-bed scene, the Grandpa, thinking he’s talking to his wife, but he’s all alone, nobody can hear him, reconciliation is meaningless now,

“I’m a fool who would give anything to have his life back. . . I hear the Ilha wind, the palm trees rustling, everything is getting soft slow bright like your eyes Marta, the waves lapping at our feet, let’s close our eyes for a moment, let’s sleep.”

My mom translated Tropicália into portuguese; I have a copy she was annotating while she worked; she wrote in the margins of the grandpa chapter,

“This is very very hard to read, too true. . .”

TOO TRUE : is that possible?

Tropicália poked at festering wounds, exposed some things never meant to be seen. . . there was so much about my grandpa — ! ! ! — . ! ! — * ! * — . . .

I never told anyone; —NO —> once, I let it spill :

I was at a bonfire with my girlfriend in high-school, Christina; I blacked out in 30 minutes, puked all over her; came to inside a freezing barn in Fort Cherry PA. . .

We were curled up next to each other on the floor in sleeping bags, — I have a picture of this; — half-consciously I started barfing confessions, spilling every secret I’d ever kept. I don’t remember what she said.

By daybreak, I was ashamed. Everything that was so important to me was immediately diminished. . . the lingering taste of poison on my breath. . .

Maybe some things should remain UNTOLD. . .

(3) — WHY AM I STILL TELLING. . . ?

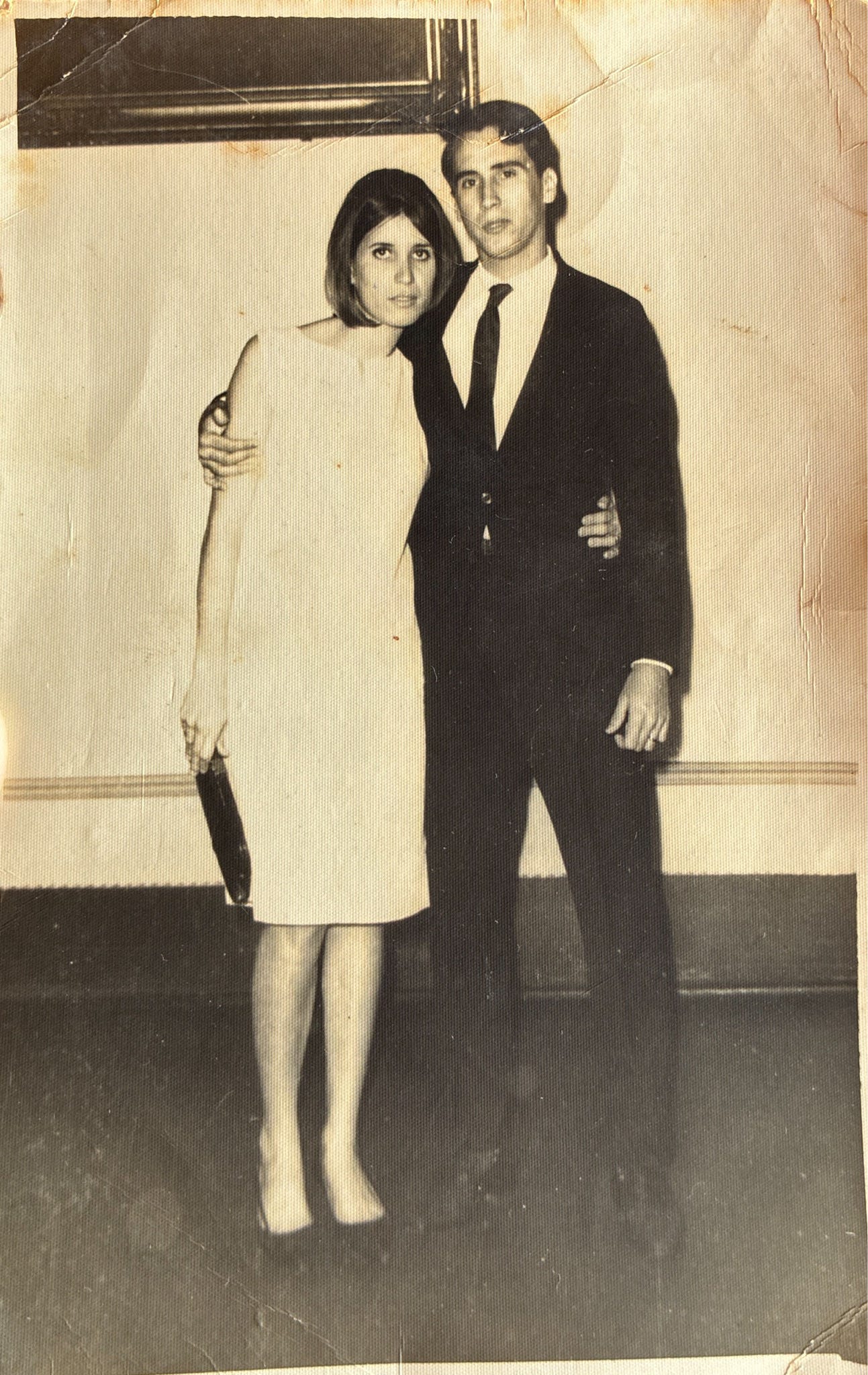

MY FAVORITE PICTURE : my grandparents on their wedding day :

on the back, in my grandpa’s careful handwriting, in red ink,

“your kids, Hugo Areias da Cunha & Maria Lucia Von Klay Alves da Cunha offer this with care to their father and father in law. Memory from our wedding 24 June 1966.”

This photograph was given as a gift to my great-grandpa Sebastian : — I know almost nothing about Sebastian ; my great-grandma Celeste dumped him for reasons difficult to parse : one story : her hoity family noseupturnedly spoiled the match. . .

That don’t make sense to me. Celeste ended up a single mom living on the Morro do Dendê, so broke my grandpa, as the oldest, would dinnertime=slaughter street pigeons.

In Celeste & Sebastian’s wedding picture, he looks small, — mustached & morose; — even removing retrospection, it can’t possibly bode a happy life.

On the way to my American grandpa’s funeral, 4 November 2019, I asked Vovô Hugo how Sebastian died. Tuberculosis. Alone at the hospital. No visitors allowed. Got sick : Hugo never saw him again. . .

“Were you sad?” I asked him.

“I don’t remember.”

LET’S LOOK : my grandparents. . .

Gaby saw this picture, said, “oh my god your grandma was a baddie.” . . . my dad saw it : “wow, Hugo was handsome, no wonder he was getting all that pussy.”

Before the alheial Ilha hoes & dead-beat drunken worklessness: UNION.

My grandma trusts him ; she’s 20 ; her head tilted toward him : she was laying it on his chest a moment before the photo,

I met this man on a bus fell for his wily talk about my dreamy eyes, everyone says it’s a horrible idea he’s a bum like his dad but I have to maybe — PICTURE! —

lifts her head somnambulantly, grips his waist, hope overrides fear.

Lucia has a secret. Can you tell in her eyes? She’s pregnant. — Concealed fathoms : the angelic ingenue sad eyes warning her future // his secret : A SHADOW : glimpse a man behind the man // darkness like a cumulonimbus gravid over Guanabara Bay. . .

Don’t let fate’s cement harden your LOOK . . .

Favor a different reading : concealing something else, — check Hugo’s expression & the left crinkle of Lucia’s cheek, her lip rising in a barely visible smirk. . . — they were LAUGHING, forced themselves to get serious for the picture.

The real secret : they had FUN on their wedding day . . . : . . . Lucia meets Hugo on the bus, marries him because he’s funny & handsome & she’s pregnant. — — >

/ / / myriad=different lives could’ve bloomed / / / i’m interested in all those people / / /

/ / / memory=stewardship — ? — / / / i wanna make sense of what i’ve witnessed / / /

They are looking at ME. — Pick up the picture. — You see US. — NOW WHAT?

Love how you adapt your writing to the digital medium. Really fun and fragmented — and the quotes from Tropicalia (more strightfoward) end up making a nice contrast. Best passage in this is all you guys holding hands and laughing and your mum losing it. Hilarious

This is such a gorgeous piece, very jealous of your courageous usage of language and punctuation