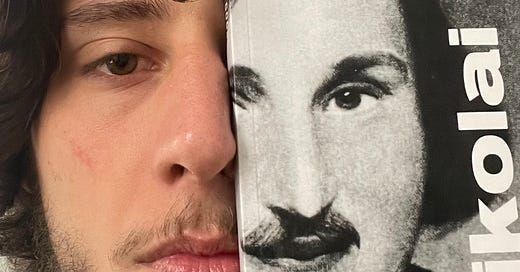

My favorite moment in Nikolai Gogol’s Dead Souls (1842) comes late in the first volume.

So this dude, Paul Ivanovich Chichikov rolls up to a small town in Russia mysteriously; he’s totally nondescript, “not handsome but also not bad-looking, neither too fat nor too thin; you could not have said he was old, yet neither was he all that young” and he got a scheme.

It’s 19th century Russia, so it’s serfdom, right? And these landowners own the peasants and they pay taxes on them. But there’s often a big time gap between the censuses, so the peasants die, but they’re not stricken off the record. Chichikov is going from landowner to landowner offering to buy up these dead souls.

One of the most brilliant things about the whole book is that we never find out exactly what the whole scheme is, what the end result of this buying-up is. But it causes quite a stir in the small town. Especially once word gets out that he bought hundreds of peasants and he’s relocating them all to a different province. People start saying he’s a millionaire, start making up stories about him. He should’ve skipped town; he overstays his welcome.

At a lavish ball, while all the society ladies are pining for him and his big bucks, his attention is firmly fixed on the town hottie, a young blondie, the governor’s daughter (whom Gogol, to whom sex and lust were ostensibly irrelevant don’t describe with any carnal vividness [to Vladimir Nabokov’s {that infamous describer of young women} dismay, one of his few complaints about Gogol’s great works is that he’s not a great describer of young women, Nabokov’s sympathies, in that regard, lie much more firmly with Pushkin who in Eugene Onegin spends five stanzas on,

two little feet! …Doleful, grown cool,

I still remember them, and in my sleep,

they disturb my heart.

And on and on and on {and of course this is quoted from Nabokov’s much-maligned translation of Eugene Onegin [I’m sorry this parenthetical break is taking so long], which I haven’t finished but which seems to me quite wonderful and brilliant and is just another reminder that the critic of literature is nothing and worthless and the only thing that matters is the artist}), to the dismay of the women,

The ladies were all thoroughly displeased with Chichikov’s behavior. One of them purposely walked past him to make him notice it, and even brushed against the blond girl rather carelessly with the thick rouleau of her dress, and managed the scarf that fluttered about her shoulders so that its end waved right in her face…

even though this young woman is bored to death by Chichikov,

while the girl yawned, he went on telling her little stories of some sort that had happened at various times, even touching on the Greek philosopher Diogenes.

I’ll come back to Diogenes cause I just realized this could be a significant detail. Just remember that Diogenes was the founder of the cynics. And the cynics’ philosophy was to be like dogs, shun accoutrements, bark at adversaries, etc.

But anyway, Chichikov pissed off the wrong set of society.

The indignation was mounting, and ladies in different corners began to speak of him in a most unfavorable way…

And soon the rumor mill starts churning and various stories get out about Chichikov. The main one being that his purpose in town is to kidnap the Governor’s daughter and carry her off.

And now to my favorite moment; there’s a gathering at the police chief’s house (“the father and benefactor of the town”) and everybody is talking about Chichikov and then suddenly the postmaster stands up and goes,

He, gentlemen, my dear sir, is none other than Captain Kopeikin!

And the postmaster begins telling a long story about this so-called Captain Kopeikin who had his arm and his leg blown off in the campaign of the year 1812 (Napoleonic wars) and now he’s destitute and scrounging for opportunity and he goes to St. Petersburg, a stunning, bustling metropolis, in his view; he wants to talk to the General, some high-up high-falutin fellow, see if he can get a little remuneration, and he pleads his case and the dude tells him to come back in a few days, and he’s so euphoric he goes out and has a lavish meal at the tavern, drinks vodka and wine, even

sees some trim English woman going down the sidewalk, if you can picture it, like some such swan. My Kopeikin—his blood, you know, was acting up in him—started after her, hump, hump, on his wooden leg—‘but no,’ he thought, ‘later, when I have my pension, I’m getting too carried away now.’

And, in a bureaucratic nightmare of course recalling Kafka, Kopeikin keeps coming back and they keep

feeding him that same dish, ‘tomorrow’

until he gets so demoralized that he skips town and nobody knows where he ended up, but the postmaster says,

before two months had passed, if you can picture it, a band of robbers appeared in the Ryazan forests, and the leader of the band, my good sir, was none other than…

And as he’s about to say, the police chief cuts him off,

Only forgive me, Ivan Andreevich… you yourself said that Captain Kopeikin was missing an arm and a leg while Chichikov…

and so,

the postmaster cried out, slapped himself roundly on the forehead, and publicly in front of them all called himself a hunk of veal.

He just totally forgot that Chichikov had all his limbs! And then the story of Captain Kopeikin never comes up again in the whole novel. It was an irrelevant, incidental texture woven into the story. Gogol constantly conjures these brief lives and brings them right up to our eyes and ears and nose and then whisks them off into oblivion, as if painting in the landscape at the edge of his world.

Now a corny creative writing teacher might say that that’s what justifies the appearance of this tale in the story, that it gives the illusion that the novel is fuller than it is at the corners. But what I love about it is exactly the unjustifiability of it. And it’s just really really funny.

Lately what has thrilled me the most in literature is the incidental and unnecessary, or when the narrator makes some insane intrusion into the story like Gogol’s narrator frequently does, such as at the beginning of Chapter 8 when he goes,

Happy the writer who, passing by characters that are boring, disgusting, shocking in their mournful reality, approaches characters that manifest the lofty dignity of man who from the great pool of daily whirling images has chosen only the rare exceptions, who has never once betrayed the exalted turning of his lyre, nor descended from his height to his poor insignificant brethren… with entrancing smoke he has clouded people’s eyes; he has flattered them wondrously, concealing what is mournful in life, showing them a beautiful man…

And after a few pages of this, he goes,

Onward! onward! away with the wrinkle that furrows the brow and the stern gloom of the face! At once and suddenly let us plunge into life with all its noiseless clatter and little bells and see what Chichikov is doing.

It’s funny I was telling a boxing client of mine that I was reading Dead Souls, and he was like, ironically, “light reading huh?” cause it has the musty reputation of a russian classic.

But Gogol exemplifies, to me, what lately seems to me the only important feature of literature: a loose recklessness, a fervid capaciousness to include all the disgusting shocking mournful incidentality of life in an unartificial, unstreamlined way. I go to the bookstore and pick up the front table novels and all it is is Blah, blah this. I was in a room. There was somewhere there. And now we have a scene. And there's these pretty little sentences.

Fuck a pretty sentence! Fuck pristine prose! I’m tired of that shit. All these writers of this artificial fiction are Chichikov. In Nabokov’s brilliant book on Gogol, he explains the russian word poshlust which can be defined as “cheap, sham, tawdry, smutty, banal, vulgar, etc.” but Nabokov acutely points out,

all these however suggest merely certain false values for the detection of which no particular shrewdness is required.

Basically what you think is fake might not be the fake you think is fake. Like he goes on to say,

trash, curiously enough, contains sometimes a wholesome ingredient, readily appreciated by children and simple souls.

I have to tell you, I like indulging in a trashy novel. I’m a simple soul. I loved The Da Vinci Code, I just listened to Gone Girl and loved it, I liked Colleen Hoover’s It Ends With Us, no bullshit.

But none of these books claim to be great literature. What Nabokov really singles out as poshlust is these books glowingly reviewed like, “A singing book, compact of grace and light and ecstasy, a book of pearly radiance.” “Beautiful novels” that are “beautifully reviewed.” That’s poshlust. That’s fakery.

It’s these novels that are Chichikov. And it’s not a trivial matter. Chichikov is nondescript and seemingly harmless, all he’s doing is buying up dead souls after all. But make no mistake, he is the devil. All he wants to do is enter, swindle, make his dime, and move on. He cares for nothing. These dead souls, names on a slip of paper, they mean nothing to him. His existence is vapidity personified.

But the remedy to poshlust, or what I’ll call Demonic Fake Literature is everything Dead Souls is doing around Chichikov. Like the postmaster’s story, or the landowner Sobakevich, whom Chichikov goes to attempt to dupe.

Sobakevich who “resembled a medium-sized bear” foists a fucking enormous meal on Chichikov; it starts with cabbage soup and nyanya,

a well known dish served with cabbage soup, consisting of sheep’s stomach stuffed with buck-wheat groats, brains, and totters

and then a rack of lamb and

after the rack of lamb came cheesecakes, each much bigger than a plate, then a turkey the size of a calf, chock-full of good things: eggs, rice livers, and whatnot else, all of which settled in one lump in the stomach.

But what really distinguishes Sobakevich is his attitude toward his dead souls. Chichikov is trying to haggle him and Sobakevich goes,

How can you be so stingy? Some crook would cheat you, sell you trash not souls; but mine are all hale as nuts, all picked men: if not craftsmen, then some other kind of sturdy peasants.

And then he goes on and on, naming the peasants with their nicknames, describing their wonderful traits, as if they were still alive. This resurrection is essential. And in perfect contradistinction to Chichikov’s banal materialist attitude.

It’s the excess in these food scenes, and the resurrection of the dead souls, and the pointless stories like the one about Captain Kopeikin, and the narrator’s digressions and extravagancies, that make this, to me, extremely exciting literature.

But maybe we have different ideas about literature. Maybe you like pretty prose, maybe you like the streamlined and sanitized, maybe you want literature from a normal person, maybe even a good person. And I don’t fault you.

But when I hear about Gogol’s biography, about what a fucking weirdo he was, and how at the end of his life (he died at 42), he burned the later volumes of Dead Souls (he planned a Dantean trilogy)—a move he regretted, that he blamed on a trick played on him by the Devil (whose existence he truly believed in)—and turned to an extreme asceticism which resulted in a hunger strike (he got so skinny you could feel his spine thru his stomach) that culminated in an acute anemia of the brain which against his will a doctor tried to cure by sticking six plump leeches on his nose; when I read that he writes in a letter to his mother,

I have a bad temper, a corrupt and spoiled nature (this I honestly admit); an idle and sapless existence… I must alter my nature, must be born and quickened anew, must blossom forth with all the power of my soul amid constant work and activity… (I shall never know personal happiness: that divine creature has plucked all peace out of my soul, and gone far away from me)…

He strikes me as totally looney and I get excited. But maybe I’m not even supposed to care about a writer’s life.

The other day mother sent me an email that included these lines:

I understand your books are fiction, but I also don't like when you say "it's not about you guys", and then we see some of our lives in there and I wanna know why do you do that?

why do you say it "has nothing to do with you guys, it's all fiction”?

I'm just curious because It’s feel insulting to my intelligence sometimes and I want to be treated fairly.

My life is blocks, is paint, is raw material.

If my work was solely biography it is boring and sanitized and lame.

Hopefully I turn all that shit into something reckless, loose, capacious, maybe veering toward insanity. That’s the kind of literature I’m interested in. Literature that is a screed against paltriness. I don’t wanna read the next-up novel du jour. There’s a dude on the Upper West Side who stays out around Gray’s Papaya. And he got a stack of looseleaf paper, a big thick stack, that he’s always scribbling and writing on, and even doodling on. That’s what I wanna read next.

We never got back to Diogenes did we?

Brilliant