NOT EVERYONE CAN GO TO THE MOON

We are living in a Doofdom. There is a type that doesn’t seem to exist anymore: let’s call him the Serious Man. Men have abdicated their responsibility to the preservation of our (the culture’s) intellectual patrimony. The reasons for this may be myriad and difficult to pin down, but the truth of it is hard to argue.

Find me a man who really knows something; most of our intelligent stock have devoted themselves to professional corporate usury (mud; mire). The rest are rotting their brains with DraftKings boosts and video games.

I overheard an acquaintance talking about how he was so tired of rewatching Breaking Bad that he finally began to rewatch Mad Men.

Not everyone can go to the moon, but come on!

Even the supposed smart ones, our scions of tech and science and politics; most are unserious craven goofy spineless blobs.

This is not good.

Is there an antidote?

BUMPING UGLIES

The narrator of Norman Rush’s National Book Award winning novel Mating (1991) is acutely aware of this man problem, and when she recognizes a serious man in Nelson Denoon, she literally crosses the Kalahari desert to be with him.

Nelson obliquely reminds our unnamed narrator of the paucity back in Dudville,

At moments everything seemed like a conspiracy against me, to force a choice, like Denoon’s theory of the characterological collapse of the male in the Western world, America in particular. As women get stronger and more defined, men get silly, violent, and erratic overall. I more than agreed… But why go on about this more than once, if the inner point was not to get me to feel panic about who else I could get if I abandoned Nelson, the clearsighted man, obviously one in a million, exempt from this piece of sociology.

The narrator of Mating is a 32 year old grad student whose name we never get.

We see her at a later point of her life and career in Mortals (2003) and we find out her name is Karen Ann Hoyt but,

Karen Ann hated her name, and that was because her mother, a simple person, at some point confessed to her that she chose Hoyt because it sounded like ‘hoity-toity’. And the name Karen Ann had been copied from some local subdebutante in the area who was always on the local news.

Karen Ann is living in Botswana in the 1980s and her anthropology thesis has just blown up: she was studying how food supplies affect fertility in hunter-gatherer tribes but found that the tribes weren’t as remote as she was expecting and her argument was otiose.

Rush’s characters are full of idealism that they try to impose on reality.

But obviously reality is always a pin in one’s balloon.

Thwarted by reality, an unserious person would take their popped balloon and go home grim & remorseful. Rush’s central characters have sturdier constitutions.

What makes them serious, settled people is their empirical and dialectical relationship to the world and each other.

Everything proceeds like in a Socratic dialogue: endless talk, endless thought, inching closer and closer to truth.

One thing the narrator of Mating cannot stand is lying,

I hate the mysterious, because it’s the perfect medium for liars, the place they go to multiply and preen and lie to each other. Liars are the enemy. They transcend class, sex and nation. They make everything impossible.

Lying interferes with the close attention required to pick up on another person’s “subtle bodies” a term that gives its name to the title of Rush’s last novel Subtle Bodies (2013),

But then her mother regularly declared that there was a mystical “subtle body” inside or surrounding or emanating from every human being and that if you could see it, it told you something. It told you about the essence of a person, their secrets for example. It was all about attending close enough to see them.

Nelson Denoon is not a liar (we and Karen become pretty sure: certainty qua certainty is not something you find in Rush’s novels but you have to become settled nonetheless, believing you have done your reasonable best to find the truth).

So basically this is the plot of Mating: our narrator hears that Denoon has started this matriarchal commune out in the middle of the desert called Tsau. She is bored, —not listless, none of the main characters in Rush’s novels are ever listless and if they are, they soon find a project to be convicted and immersed in, —and so she unwisely treks six days in the desert to find Tsau, and she does.

Her and Nelson become romantically involved and things in the commune start to break down (due mostly to masculine restlessness), so Nelson hastily tries to cross the desert on a mission to a neighboring town which fails drastically when he falls off his horse and breaks his leg. He has a mystical experience in the desert which alienates him from Karen when he returns. She ends up going back to the United States where she receives a cryptic message suggesting Tsau might need her.

Tsau might sound like a cult, but it’s really not.

It’s a marxist experiment in communal living founded by Nelson. Most of its inhabitants are poor women from the surrounding area who have been expelled from their tribes for various reasons.

There are men in Tsau but they can’t own anything and have no voting rights though they perform the most intensive physical labor (hence the ruinous restlessness).

The only makhoa (Setswana for whitey, plural) represented there are Nelson and Karen.

Tsau is a tremendous fictional construction. Rush gives us almost every conceivable detail about how the place works.

Karen isn’t supposed to be there. But her and Nelson tell everybody that she is an ornithologist who stumbled upon the place and she proves useful so they let her stay. But she asks herself, why does Nelson want her there,

Light broke. It was obvious. Denoon wanted to know what he had wrought at Tsau. What was Tsau, really? I was an almost ideal vehicle through which he could find out.

We end believing with the narrator that Tsau is a grand, noble, but ultimately failed experiment. Nelson can’t let it go, and that’s what ultimately dooms his love.

The conflict and collaboration between work and love is always acutely alive in Rush.

But the real glory of Mating is witnessing Nelson and Karen fall in love and stay in love.

In Subtle Bodies a character is eulogized with an excerpt from his beloved copy of James Boswell’s Life of Johnson (which he bookmarked at page 847 hoping to savor the end).

Norman Rush has a Boswellian orientation toward the novel. It is clear that he believes capturing a personality in its minutest detail, writing a Life, is the task of the novelist, and many of his characters are actively engaged in that process.

Whatever Karen’s anthropology thesis was, it becomes a Life of Nelson Denoon. She lavishes keen, generous, hilarious attention on him the whole book. And that is the only type of attention that will be rewarded by the reveal of those all important subtle bodies, the truth behind the mask.

Here is the moment when she feels like their love is at its highest point in the sky, its perihelion (Rush’s style is extremely lucid careening propulsive; he sneaks in his erudition in the most fluid palatable ways),

I remember Denoon as now back at his workbench and holding a piece of glass up to the light. He looked absolutely beautiful to me at that moment, more beautiful than he ever had. This is a serious man, kept saying itself to me. Other men aren’t. What I was suddenly afraid of was that this moment was our perihelion, the closest we would ever approach or be, and that everything after this would transpire between bodies farther apart. I was thinking that if you looked back over the trajectory of every mating once it was over, there would be an identifiable perihelion. I couldn’t stand the idea that this was ours. I didn’t know why I thought it was, even. My eyes were hot. I had to leave. This is all hypothetical, I said, keeping it declarative and trying to keep any note of entreaty out. But I knew better.

What distinguishes Rush from his male peers of that generation is his ability to illustrate a nuanced, dialectical, capaciously accepting and private (a couple’s language becomes hermetic, they create their own idioverse: Rush’s coinage which means a closed-loop lexicon) picture of romantic love.

I’m generalizing of course, but it doesn’t seem to me that Roth or Updike or Cormac think that they can learn all that much from women, —except in a way that is alheial or occult.

Rush’s characters believe they can learn about reality from women, and they do.

And eroticism for those other guys becomes something mystical and perverse. For Rush, sex is just another part of the dialectic, a continuation of the conversation.

Nelson and Karen never stop talking, joking, discovering more about one another on a level of mutual respect that doesn’t preclude annoyance disgust embarrassment (this is what I mean by capacious: making room for disappointment past the ick),

He loved me. I shouldn’t be upset. Then he confessed for the second time he regretted giving me the impression when we were discussing Middlemarch that he’d finished it. Before I could remind him that he’d already confessed this he was going further, saying he’d never even begun it, that he knew what was in it only from what he’d picked up from other women discussing it. But now he was going to read it, he swore. Here a blur ensues. We went on to other things.

Here is when Nelson first says I Love You,

Something fell off a shelf in the middle of the night and when I said, What was that? he said The scales falling from my eyes. I love you.

FOR ELSA, BEAUTIFUL AND GOOD, PERFECT FRIEND, WITH GRATITUDE

There is a not uncommon critique of Mating which jives with this One-star-take on Goodreads,

This man becomes the centre of her being and the motivation behind her every move - including walking solo across the desert, almost at the cost of her life. I tried to push through, but her internal scheming and obsession with this man became sickening, pathetic, and offensive to me as a woman.

(This seems to be the reaction of someone who unfortunately has never found a potential mate of desert-crossing worth.)

But I can see why somebody would find the following biological reductionism of the kind Karen Ann engages in a bit distasteful,

I had to realize that the male idea of successful love is to get a woman into a state of secure dependency which the male can renew by a touch or pat or gesture now and then while he reserves his major attention for his work in the world or the contemplation of various forms of surrogate combat men find so transfixing. I had to realize that female-style love is servile and petitionary and moves in the direction of greater and greater displays of servility whose object is to elicit from the male partner a surplus of face-to-face attention… Equilibrium or perfect mating will come when the male is convinced he is giving less than he feels is really required to maintain dependency and the woman feels she is getting more from him than her servile displays should merit.

Personally I find it thrilling and funny (it’s so obviously tongue-in-cheek: the contemplation of various forms of surrogate combat men find so transfixing); and this is a very smart, cerebral narrator acting irrationally and trying to justify her behavior by the most rational means possible.

When Nelson Denoon is in the hospital after his disastrous venture in the desert, Karen considers an insane plan for continuance,

This was connected with desperate fantasies I was having vis-a-vis his seed, assuming the worst had happened. It humiliates me to admit that I was wondering if I could get him erect and then get over him and capture his seed. I could only contemplate doing this if first I established I could get him erect.

Karen Ann is a hopeless romantic. And as we read more of Rush’s work, it becomes clear he is a hopeless romantic himself.

For good reason!

When he was 19 he walked into a building at Swarthmore College and saw a young woman chatting with a circle of potential suitors. He interrupted one of the young men’s questions and dunked on him, gave him a reading recommendation and walked away; Odysseus slaying Penelope’s suitors.

The young woman went back to her dorm room and told her roommate that she found the man she was gonna marry. And she was right.

That’s how Elsa and Norman met. They’ve been married for 70 years!

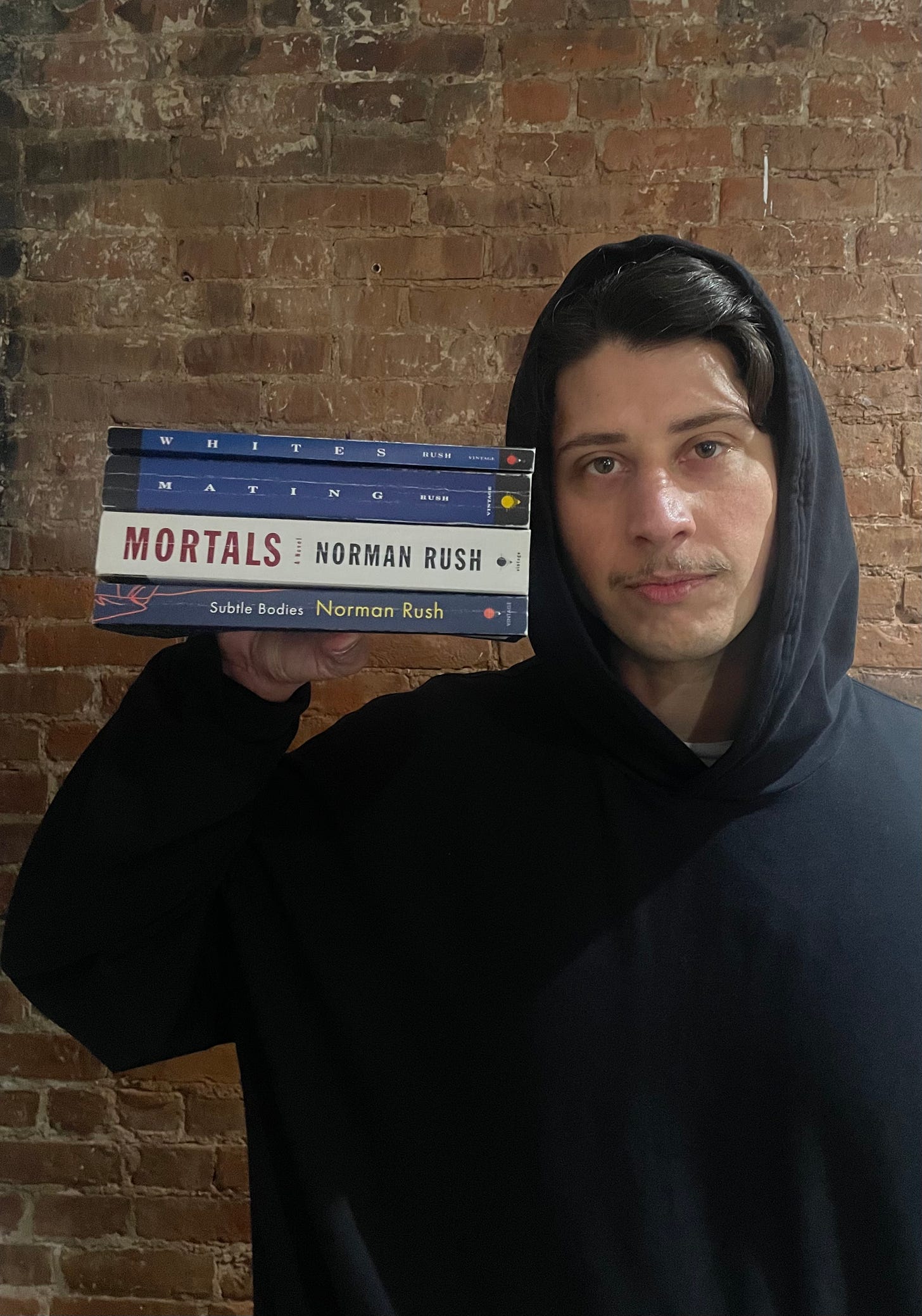

Norman Rush didn’t publish his first book, Whites (1986), until he was 53.

For those of you keeping track at home, that’s a very late debut. Which I think is an argument for the primacy of prose literature over any other art form. Precocity is the domain of music, poetry, and even comedy and the visual arts.

One jocund youthful day the afflatus might bong you and you’ll spit out some eternal jewel.

That’s pretty rare in prose literature (really only Frankenstein comes to mind as a counterpoint) because the name of the game is life experience and labor.

By his own admission Norman was wasting much of his time with over-Joycean stories,

James Joyce was a wondrous and calamitous influence on me. Interspersed along the way—having a family, running a book business, too much reading and drinking, and too much perfectionism. And then, chiefly and for much too long, I wrote agonizingly experimental stories that simply baffled editors.

Elsa told him,

She said to me, Consider maybe that there are some very smart people out there who are not interested in stories that require a seminar.

But the breakthrough came when he decided to write the first story of Whites in his wife’s voice, the voice he went on to use for Mating,

But the real model for the narrator—I've hardly tried to hide this—was Elsa. Her fearlessness of thought; her determination, almost to the point of parody, not to be deluded, tricked, deceived; her comic sense of life, and a totally empirical kind of intelligence, as opposed to Denoon's more theoretical intelligence. She's pretty much a straight lift.

He profusely dedicates Mating to her,

Everything I write is for Elsa, but especially this book, since in it her heart, sensibility, and intellect are so signally, —if perforce esoterically, —celebrated and exploited. My debt to her, in art and life, grows however much I put against it.

(He beautifully dedicates all four his books to her.)

The most uxorious (wife-obsessed), —and I think the best, —of his books is his follow up to Mating: —Mortals which was published in 2003.

Mortals is a re-telling of Paradise Lost from the very claustrophobic third person perspective of our Adam, Ray Finch, a Milton scholar slash CIA agent based in Botswana who is completely obsessed with his Eve: his wife Iris.

But like the narrator of Mating tells us,

One difference between men and women is that women really want paradise. Men say they do, but what they really mean by it is absolute security, which they can obtain only through utter domination of the near and dear and the environment as far as the eye can see, how else?

Ray is the ur-Man (and I use this phrase to suggest that across his four books, Rush is trying to paint the picture of the eternal man and the eternal woman, a primordial married couple in shifting guises like in Finnegans Wake, and I would not be surprised to find out that is exactly how he intended it; I was counting the chapters of all his books trying to find a pattern: Subtle Bodies is 53, Mortals is 38, Mating is 8, which adds up to 99; Whites which is a book of short stories doesn’t number any of the stories but on the title page there is a single number: 1. Across four books he has put out 100 total chapters. Serendipity is not so exacting.)

Ray is obsessed with control.

At the beginning of the novel he doesn’t realize that what is making Iris wicked & away, eager to wriggle out of his close scrutiny, is the fact that she loathes his job. She is tired of the lies and mystery necessary to his profession. And she is very lonely in Botswana.

Ray considers the problem that was very relevant to Adam in the garden,

The question of women as a subject came down to their unhappiness. And what was happening was that the general unhappiness of women was turning into a force and developing institutions and mandibles whereas before it had been a kind of background condition like the temperature, as he had thought, something that rose and fell within certain stable limits. He thought of his mother’s unhappiness. Iris was not what he would call a feminist and yet, if he was anywhere near understanding what was going on with her, she was part of this great unhappiness.

But the problem is that Ray is too trapped in his own patterns of thinking to do anything about her unhappiness in the real world.

To Iris at the moment, he is ineffectual and useless; one could even say unserious, which is the worst position for a husband to find himself in.

Iris is eager to be tempted.

Enter Satan: Dr. Davis Morel.

A DIGRESSION ON WHITEY IN AFRICA

Mortals struggled critically from its own ambition.

The normally astute John Updike succumbs to a little jealousy in his review which leads him to the laughable claim,

Ray’s apologetic, I-hate-myself attitude about involvement with the agency seems, after September, 2001, rather dated; instead of being considered too meddlesome and sinisterly omnipotent, the C.I.A. appears to have been, with other national watchdogs, sound asleep at the switch.

What Updike doesn’t seem to realize is that the bumbling and needless nature of the CIA’s activities is exactly what makes it so pernicious, something Rush captures perfectly.

Updike and Rush are almost the exact same age. Mostly Updike confined his domestic work domestically to Pennsylvania and environs (and some of his work is very good).

But before we move on, let me quote you some parts of his attempt to represent another culture in his 1995 novel Brazil.

Rush wrote three books about Africa and not once got remotely as racial as Updike gets here.

Here is white girl Isabel checking out Tristão whose father has “pure African blood, as pure as blood can be in Brazil”,

Now she studied his face: the full Negro features were carved on a frame that had never known gluttony, with a childish shine to the prominent eyes, a rampartlike erectness to the bony brow, and a coppery tinge to his crown of tightly kinked hair…

And a couple pages later when they have their eternally incriminating lusty interracial bang,

If she was a virgin, fucking her became religious, a kind of eternal incrimination. But his blood, helplessly pounding in the yam he carried before him… her white buttocks parted, showing a vertical brown lining between them, a permanent stain of skin around her anus, slightly disgusting him.

What do you think his yam is? Let me stop.

But it’s clear that Updike’s experience of another culture is an exotic toe-dip.

I don’t know for a fact, but I don’t think many real brasilians were consulted in the making of Brazil.

So what are Norman Rush’s African credentials?

In the mid 70s he was at a party and he and his wife got into a political argument with this dude. And if there’s one thing Rush couldn’t be more interested in it’s politics. He even spent two years in prison in his teens for dodging the Korean War draft.

But it turns out the dude was running the Peace Corps and he was looking for a husband/wife team who had been together for at least twenty years to place as directors in Africa.

They went to DC for the interview, treating it carelessly, and they crushed.

They were supposed to be placed in Benin, but they got their Bs mixed up and ended up at the Botswana guy’s desk. He loved them, and sent them off.

They spent five years from 1978 to 1983 working in Botswana. The work was daily and grueling. They took a single one week vacation in five years.

Rush didn’t write a word of fiction while he was down there but he filled up notebooks upon notebooks and when he got back home he was a different artist.

Whitey in Africa, or in any other culture is a trepidatious proposition.

But Norman Rush is a Great American Writer because of his engagement with Botswana rather than despite it. He recognizes the American yearn to remake the other in your own image; the pitfalls of Americans looking in other cultures to find themselves.

I actually knew about Botswana because in highschool after my French teacher Mr. Swaykus died, —and he was my favorite teacher after my English teacher Miss C died (yes, my two favorite teachers died before I was a Junior; 30% of the whole faculty), —we got a substitute who ended up staying on for the rest of the year.

His name was Mr. Leonard and he was from Boston, but he had lived for ten years in Botswaner (which is what he called it in his thick accent). He didn’t know any French at all, so he would spend most of the class regaling us with tales about Botswaner.

I remember thinking, If this goofball can spend a decade out in Africa, anybody can live anywhere.

He ended up getting fired at the end of the year which was very sad for me because I got a big kick out of him. He told me with tears in his eyes. He couldn’t believe it.

I had to really bite my tongue not to say, Well… you don’t speak any fucking French.

The opening line of Mating is

In Africa, you want more, I think.

But Rush has no illusions about America’s complicated and often pernicious influence abroad. We are constantly faced with the tension inherent in the cultureclash.

Sometimes a lakhoa (Setswana for whitey, singular) acts foolish and Rush makes sure we’re mortified.

Here’s one half of a feuding couple in the story “Near Pala” in Whites describing what they did with a papaya tree that looked dead in their yard,

So we hauled and pushed on the trunk of the poor tree and strained and pulled it over—uprooted it, Gareth and myself. It was his idea: we must just straight off do this, get it over. Then, with the crash, the servants come out. They had funny looks on. Dineo said so quietly, ‘Oh, Mma, you have killed the male.’ We didn’t understand. It seems the pawpaw grow in pairs, couples, male and female. The male tree looks like a phallus—no foliage to it really. The female needs the male in order to bear. They take years to reach the heights ours had. Then the female died. The staff had been eating pawpaws from our tree for years. It was a humiliation.

Rush believes it is essential to familiarize yourself with the culture you are inhabiting. A frustration expressed by both Karen and Ray is the lack of a universal language, how tedious and frustrating it is to have to translate, interpret, communicate across gulfs.

It is part of the world-governing dialectic that Rush believes in: being confronted with strife or difference and re-evaluating your own behaviors and expectations.

The impulse is anthropological; you can clearly see that by the glossary of Setswana terms in the back of Mating and Mortals.

But there is a barrier against total immersion.

Some British actors by random accident end up in Tsau. They’re only gonna stay for a few days and they decide to put on some scenes from Shakespeare. Nelson Denoon has beef with the main actor who is brilliantly named Harold.

So he decides to put on a counter production of a style of theater he has been working on with the women in Tsau which is based strongly in local traditions.

It doesn’t go well, Karen is completely embarrassed,

I felt like shriveling and concurrently felt disloyal over my embarrassment, seeing myself as callowly identifying with the white West and turning my back on the person I lived with because his attempt to tease out and concretize the voice of the formerly oppressed was too hubristic for me, at least when I had to witness the attempt not en famille but in the company of educated members of the West cultured in ways I happened to be impressed by. We all love hubris in a mate but we prefer it to be in moderation.

As immersed as he’s been in the community, his show of complete submersion and integration is a total flop because he doesn’t have the right to the traditions and experiences of the people he’s devoted his life to championing no matter how much work he does on their behalf.

SO LATE THEIR HAPPY SEAT

Ray Finch is a CIA agent in Botswana.

His bored wife Iris starts going to therapy with this newly arrived American, the handsome, upright, and intelligent Dr. Davis Morel, who is quixotically intent on ridding the Batswana of their Christianity.

Morel thinks Christianity is all a big lie. He is trying to convince people that Jesus was an apocalyptic Jew whose sole philosophy was that we could convince Yahweh to intervene in our corrupt human society by acting like little obedient babies.

He thinks Jesus’s mission is a failure,

The story of Jesus the Jew is the story of an experiment in mass psychology that fails. It fails. It is a complete story whose end features the disciples of Jesus denying him, and running away, and he himself, the poor man, asking Yahweh why he has forsaken him, why he has not come downstairs, alas, alas, Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani? are the hardest words to hear.

Paul is really the one who evilly adapted other philosophies and religions into the malevolent thing that become Christianity.

Morel thinks explaining that to people will divest them of their belief.

We get his whole theory in fascinating detail.

You do learn things in every Rush book (and what is a novel that teaches you nothing even worth?).

Like we get the story of Nongqawuse, a Xhosa woman who, inspired by a vision of Jesus, convinced the people in her tribe to kill all their cattle in order to bring about God’s kingdom on earth. It was a complete disaster and led to decades of famine. This is one of Morel’s examples of the bad influence of Christianity in Africa.

Ray Finch knows Morel is a problem before he even knows he’s a problem, and he starts spying on him.

Through a complicated series of events, Finch’s spying leads a UK-educated Batswana named Kerekang on an insurgency mission in the countryside, setting fire to cattle and property. Moronic CIA meddling goes horribly wrong.

The then-eminent Michiko Kakutani also had mixed feelings about Mortals,

We are stuck for the duration inside Ray's head, or rather, since Mr. Rush has opted for a stilted third-person narration, we are stuck inside a tiny, claustrophobic room with Ray, one of the most narcissistic, self-deluding and defensive heroes to come along in a while.

She’s right about most of this but wrong in giving these facts a negative valence.

For one, Ray is not supposed to be good. He is an annoying supra-uxorious American CIA agent in Africa who has needless beef with his brother and who metaphorically suffocates his wife.

But the success of this book lies in seeing Ray suffer through this morass and step into a more morally deft life on the other side.

And the narration is not stilted, it is painstaking and fastidious, it accumulates like Knausgaard, and the writing starts off deceptively simple and builds into something like a fluffless ornanity.

Which makes it so that when the narrative voice is beautiful, we don’t feel like we’re being taken on a lyrical flight of fancy, it feels like the most natural thing in the world. And it also allows for the sharpness of the dialogue to stick out like light in a chiaroscuro.

Here is a moment when Ray is overcome by sorrow later in the book,

His eyes were filling with tears. It was unusual. It was philosophical. It was a generic sorrow for human beings caught in situations like theirs, the three of them, humans making declarations they meant at the time and that got undone and swept away by perverse events, the perversity of the future as it arrived so clumsily, giantly, smashing things. That was what it was. Except for the part that was about self-pity, that was what it was.

Does this sound like the most self-deluded narrator ever like Kakutani suggests?

It sounds more like Proust to me, emerging into clarity.

Lucidity is obviously a virtue for Rush and the characters he wants us to see as successes achieve this.

Here is Ray and Iris having a conversation while she is in the United States with her sister, their first time apart in 17 years,

The love of a woman with a funny mind is the definition of paradise, he thought…

‘This is what I want,’ Iris said. ‘If I die first, this is what I want you to do. Take my ashes and put them in an urn on the coffee table and then every now and then lift the lid and shout the latest down into it, whatever is going on.’

‘Then you do the same.’

‘Don’t say it. I can’t stand if you die first. It’s worse if you die than if I do.’

‘Please don’t say that and please let’s not have this conversation when you’re there and I can’t hold you.’ Save you, was what he meant.

‘I’m wretched without you,’ she said, her voice very low.

The love of a woman with a funny mind is the definition of paradise. Can you imagine Updike writing something like that?

What comes through strongly in all of Rush’s writing is that he knows what it is to profoundly love and respect a romantic partner.

We know the entire time reading Mortals that Eve is going to eat the apple. Rush recognizes like we all should that the story of Eve’s transgression is about (to not mince words) Eve fucking the devil.

But it is an excruciating process. Especially since we see how keenly Iris and Ray love each other. And they do, despite how annoying he can be.

Like Ray, we know she’s going to this brilliant, handsome therapist and she’s saying things like,

She sighed, turned, and said musingly, ‘Do you know that I don’t know if your penis is particularly large or not?’

It is, by God, he thought, outraged. But what was this. It was pure provocation.

She said, ‘You claim it is, but how do I know, really? I’m almost a virgin, I mean I was almost a virgin when I met you.’

He was agitated. He had to keep himself under control. The tone had to be light. This was new. He could say, ‘Gulp he said,’ but that was witless. Anxiety was doing this to her. She was flailing. She was being random.

I was pissed off on Ray’s behalf just reading that.

But she’s right! There’s nothing exactly wrong with what she’s saying. The provocation there is that she’s dealing in the truth. Her transgression is saying the things she’s not supposed to say out of benevolent-lying.

Rush is very attuned the comedy of sex. That exchange took place in a chapter called, “I Would Like to Reassure About My Penis.”

My favorite story in Whites is the last one, “Alone in Africa”.

Frank is an American dentist in Botswana whose wife is out of town. We know from an earlier story that his wife is an avid extracurricular seductress. Completely unlike Iris, she makes a sport out of cheating on her husband; that’s her cure to boredom and the nagging metaphysical questions of life.

Frank doesn’t know any of that, he’s never cheated on her.

But she’s alone on vacation in Europe and he’s all alone in his house and a young local woman shows up at his door under the guise of being his cook while his wife is gone. Really she wants to have sex with him for money. The woman is pushy and he decides, What the hell.

As the opening of Subtle Bodies tells us,

Genitals have a life of their own, his beloved Nina had said at the close of an argument over whether even the most besotted husband could be trusted one hundred percent faced with the permanent sexual temptations the world provided.

Thankfully there’s condoms in the house because his wife,

was a variestist who came up with fantasies that involved condoms. How many guys with postfertile wives would have condoms lying around in an emergency like this?

We know, obviously, that she really has condoms to betray him.

(Also this optimistic balance is alive throughout all of Rush’s work. Yes Frank’s wife is betraying him, but here is a little positive comeuppance just for him.)

But as they’re about to get down to business, the young woman, Moitse’s little sisters start making a racket outside, teasing her. Which draws the attention of the nosey superChristian next door neighbor.

Frank rushes to the door in his robe, condom still on his dick and the neighbor basically barges his way in. Frank is sure he’s gonna walk in and see the naked Moitse and her little sisters hiding under the kitchen table but when they walk in,

Moitse, fully dressed, was sitting at a stool by the sink. She had a towel across her knees and the bowl of sugar peas in her lap. On the floor, sitting facing her with their legs straight out, were her sisters. They were watching her face fixedly. She was showing them how to string peas. Each of the younger sisters was clutching a handful of peas. There were little piles of strings on the floor. Christie [the neighbor] was silent.

And just as Christie walks away from his house,

A draft stirred Frank’s bathrobe: out of the folds the condom dropped, like a fallen blossom.

But now Moitse is gone. She had to take her sisters home. We think. But as Frank lays down to go to sleep,

There was a scraping sound at the window above him, the sound of nails on the flyscreen. He recognized it. He sat up straight. She was back. She was back.

Characters in Rush always come back.

FORTY DAYS IN THE DESERT

If I had to guess what Norman Rush’s favorite part in the bible is I would say that it’s the time Jesus spends in the desert before he begins his public ministry.

Nothing will reveal the truth about you to you like hunger desolation silence and suffering. Christ is tempted by the devil and it solidifies his mission.

The narrator of Mating ventures out into the desert and it solidifies her mission to get to Tsau and love Denoon. After almost giving up on her sixth day in the desert she decides to walk all night as long as her ox can handle it,

Night came and the idea of camping was unthinkable because, as I saw it, only impetus could save us. We had to reach Tsau. We would go with the water we had and forget about the last water point…

And the final reason for continuing was that a vulture couple had picked us up during the day and was following us. That was not what we needed. And vultures leave us alone during the night. They go someplace and roost. There was a chance, I thought, that something more attractively protomoribund than we two might detain them on the morrow.

Ray is also sent out into the desert because of the business he inadvertently initiated with Kerekang.

Shit goes totally wrong and he ends up the prisoner of a koevoet: a South-African counterinsurgency police force; in a scenario Kakutani describes as part of,

oddly generic references to political and ethnic tensions in the country during the early 90's

When the conflict could literally not be more peculiar and specific.

This was after traveling for several days in a car that Iris helped him pack up. She also packed him some reading material, including one novel: Madame Bovary.

A novel about a famously adulteress young wife. Which of course drives him crazy.

He has lots of time to think in prison which leads to thoughts like,

Death was bad, but not as bad as someone else licking your wife’s cunt.

But guess who gets thrown into his cell one day? Dr. Davis Morel. Whom Iris sent looking for him.

With lots and lots and lots of time to shoot the shit, they get down to brass tacks,

Ray said, ‘Tell me now. Be me. Be me, asking.’ He was willing the truth to come out of Morel.

He could feel Morel composing himself.

Morel said, ‘Okay then. It’s true, I love her. We are lovers, yes. So okay.’ It was clear he had spoken slowly to keep his tone under control.

‘I can’t believe it,’ Ray heard himself say.

…

‘No, but your intentions. I mean, you want to have her, take her. That is, you’re looking at this as serious, a permanent thing.’

‘That is what I want,’ Morel said.

It was difficult to keep talking. He made himself go on.

‘You’d marry her, you’d like to. Once I’m on the other side of the horizon.’

‘You know we haven’t advanced to that. I don’t want to flatter myself and say I know more about what she wants than I really do. But, yes, of course I would. Of course.’

I have to say, I was completely heartbroken by this scene. Despite expecting it for the first 450 pages of the book; after being stuck in Ray’s head for so long I found the confession unbearable.

Ray comports himself bravely and heroically in the midst of the war and realizes what he should’ve realized all along, a truth that would’ve saved him from all this Iris-grief: he should leave the CIA.

Why did Iris betray him though?

Here she is, like Eve explaining herself,

‘Also you were away when this was developing. I mean when it got serious, this serious. That’s no excuse, I know. But the truth is I wanted to do it. I wanted that. I was attracted to Davis. I was in a state of temptation that turned intense sooner than I was prepared for, and you were away. It turned intense. What I thought was that I could do it and then see, see how I felt… and I think, I think maybe I was assuming that the chances were okay that it wasn’t going to be the greatest thing in the world and that I would conclude that, finally, but in the meantime I would have gotten something out of my system. I know this is crude, me being very crude. I think it’s the kind of thing men do and…’

‘You have to stop for a minute. This is hard for me, my girl, my girl. Ah Jesus.’

‘And I don’t know if maybe I thought once I had been through it, through something forbidden, that it would be over and we could be back together.’

The time in the desert changes everything.

HOPE SPRINGS ETERNAL

Rush’s characters are frequently confronted with their own personal doom, but it is never a dead end because they are adaptable. They believe in the process of adjusting to what the world gives us because they believe in truth and knowledge.

And they believe in the future of the world.

In Rush’s last book, Subtle Bodies (2013) the final manifestation of Karen/Nelson and Ray/Iris (who all have discussed having children), Ned and Nina are trying to get pregnant, and we are led to believe that they succeed.

There’s a reason Christ, —in the world of Rush’s novels, —is not a salvific presence; we are the only ones who can save ourselves, by seeking the truth and acting on behalf of that truth.

It is an old-school radically un-nihilistic philosophy: you can know and you can act. And your actions matter. This world is bereft of fate; it is pure contingency. Christ the boots-on-the-ground rabblerouser, the desert-endurer is the figure of interest, —not the messiah risen from the dead.

So it’s not surprising that despite the hellmouth (Rush’s coinage) these characters confront, every book ends on a hopeful note.

Karen might’ve gone off to the United States in Mating but the book ends with her receiving a message from Tsau and deciding at the end to return,

I’m coming.

Why not?

And in Mortals we see her years later, a Serious Woman, leading the charge Denoon started with him diminished and sickly but still by her side,

They’re a success already, visually, Ray thought. Together they communicated valiancy, if there was such a word, that and an impression of worthiness and splendid weariness, aided of course by what the viewer knew about them, but still… They had glamour, this pair. They really did.

Subtle Bodies ends with the main guy Ned at a protest against the Iraq War that he organized, believing that the protest will be efficacious in stopping the war.

The last word of the book is a positive optimistic “No” (there’s Joyce again, he’s everywhere in Rush).

Which of course has a ring of irony because we know what happened. But I don’t think it’s meant as a cruel joke, I think it’s a paean to continue to try, try, try.

Don’t become complacent in the struggle to rid the world of cruelty and dishonesty and stupidity.

But my favorite ending is that of Mortals.

The most moving part of Paradise Lost is what happens after the fall, after Adam and Eve have the first nasty fuck in human history and then they’re vituperating each other and then Eve comes up with her little schemes to stick it to God.

But then Adam says, you know what, let’s chill, we can endure this life, together. And he forgives her,

But rise, let us no more contend, nor blame

Each other, blamed enough elsewhere, but strive

In offices of love, how we may lighten

Each other’s burden in our share of woe.

Ray, —gone from the CIA, separated from his wife for the first time in his adult life, working at a school he founded out in the bush around South Africa (trying to do good!), —is changed; and all he can think about is forgiving Iris, he wants her again for them to mutually lighten their share of woe, and he sends her a letter,

I am writing Lives, just my brother’s so far, and it’s not finished. There will be more.

I am full of love for you, but you can come however you feel about me. I have a way to let you know where I am and I will use it in a short time.

Love,

Your husband,

Ray.

And if we’ve learned anything about Rush, Iris will go be with Ray again.

They will love each other. And they will try their best to do good in the world.

Norman Rush has written four books that serve as a manifesto against Doofdom. Here are serious people living seriously. Not serious in a dry pedantic way. Serious as funny, error-prone, romantic, and striving. We can still be good, we can still be smart, we can keep learning about the world and each other.

Things are never as hopeless as they seem.

Your actions can save you.

If you’ve ever read any Rush please comment and let me know what you thought. And if you have any longer form matters to discuss about life or literature please email me at contactharoldrogers@gmail.com.

Great piece. I like this distinction: "Here are serious people living seriously. Not serious in a dry pedantic way. Serious as funny, error-prone, romantic, and striving." Definitely makes me want to read Rush's work. Also, this: "What comes through strongly in all of Rush’s writing is that he knows what it is to profoundly love and respect a romantic partner." is a quality I feel as though doesn't appear enough in fiction these days (maybe?) but would like to see more of.

Excellent work. I have a copy of Mating lying around here somewhere. I’m excited to pick it up.