1. IF U COMING IN HERE U BETTER: ABANDON HOPE

DR. SAMUEL ENNER had an infernal year,

What happened that year made me into something different. I felt like a caterpillar winding myself into a cocoon, settling in, losing my appetite for leaves, forgetting my fear of birds, contracting my soft green body into a hard brown shell, erasing my caterpillar memories, saying goodbye to the sun and rain, becoming a pupa. Soon I will be lost to myself, and before that happens, I want to write this book.

Weak in Comparison to Dreams (2023) by James Elkins and published by the Unnamed Press is Dr. Samuel Enner’s account of the year he spent visiting zoos, slowly losing his reason.

We know we’re about to be on a hellish spiral because as he’s driving thru the woods in Estonia, the diritta via ain’t nowhere to be seen,

and that was when I realized I had lost sight of the road. The forest was all around me, symmetrical in every direction. . . When you lose your place in the world, you suddenly wake up, as if your normal life had been a dream. At that moment I was the man who came to his senses midway along his life’s journey, in the middle of a dark forest.

Dr. Samuel Enner is an expert on amoebas and microbiotic lifeforms, but he gets sent, —he’s not sure why, he suspects it may be his overlords out to get him, —to zoos all around the world to check on animals engaged in odd behaviors that might suggest they’re in distress.

He lives in Guelph, Ontario, but he don’t got much hankering him homeward anyhow, his wife Adela don’t love him anymore,

my life with Adela was almost back to zero. When we first met, we were at zero, naturally, because we didn’t know each other. Then we felt some love, +1, and we added more, +3, +5, +9, and soon we were adding up to something. There was incrementally more love each day, 32, 36, 47, it surprised us, 50, 60, 70, building like one of hose pressure meters on submarines in old movies, and suddenly it was much more, 100, 150, jumping up to 300, say (when Adela was pregnant and we were too nervous to know how happy we were), then up to 500 (the year Fina was born, a year of continuous smiling), even 900, unprecedented, wonderful (that would be the last summer we were really in love, a great summer, long days when nothing much happened). Then the meter started to fall. . .

And his daughter Fina is in college.

His only real companions now are Veepesh and Viperine: 2 interns from back at the lab at Guelph who prepare packets of papers for him to prepare him for his zoo visits and whose conversations he imagines;

and also, the people at the zoo he meets with and has to convince that he’s some sort of expert in this distressed animal business.

THE FIRST ZOO DON’T seem so bad.

Most of the Estonian animals are retreated into their enclosures,

It was hard to see if there were animals inside the darkened cages. For some reason the zoo was in a forest, and more of those depressing Estonian trees shaded the displays.

But this is a book of escalation & deterioration.

Each chapter is a prelude followed by a dreamy fugue.

Samuel has a recurring dream that he’s in a forest; first he thinks it’s in Watkins Glen, New York where he grew up, and every page of the dream has a different picture of that forest, but he realizes, at the end of the second dream. . .

You have never seen this.

You have never walked here.

THE NEXT ZOO HE goes to is in Helsinki where he tries to piss off his liaison, Dr. Pekka,

Something about Pekka offended me. At the time he seemed competent, probably boring, but well informed and friendly, and those were qualities I’d once had. Afterward I thought maybe it wasn’t Pekka who’d set me off, but the world he lived in, that cold island where a babylike animal imprisoned other animals.

There is something remarkably inhuman about these zoos, a feeling that accelerates as you progress thru the novel; in the main body of the book, we get lots of pictures of the animal enclosures, but none of the actual animals: everything is a cold, barren prison;

as if life had been raptured,

For Pekka, taking care of animals was like maintaining your garage. You sweep it out, fix a shingle, paint it every couple of years. You don’t hope for much from it because it’s only a garage.

After the zoo visit, for what Samuel interprets as a punishment for being an asshole, Pekka invites him to come to the extreme sauna with him and puts him thru the ringer,

I felt done, like a vegetable that’s been over-steamed until it’s pretty much mush. Then it was time to go back to the sauna. I followed placidly, like a prisoner, like an addict.

After several more rounds of painful heat and piercing cold, during which the oversized thermometer on the wall registered as high as a hundred and twenty Celsius, we went back to the showers, which I could hardly feel. As if the water were air. My skin had gone numb. It felt soft and lifeless like damp cardboard.

— Well, I deserved that, I said, as we walked down a darkening street.

Every zoo visit becomes a more extreme comedic horror; something is burning thru the synapses of Samuel’s reason. . .

he is an animal in distress.

2. ANIMALS IN DISTRESS

ONE WAY TO KEEP the first person POV consistently popping is to cede ground to different material.

Like I said before, this book is packed with pictures. . .

3. INTERRUPTION: TELL EM HAROLD.

; — I SHOULD SAY HOW I found this book in the first place.

I was in Rizzoli on 26th Street in New York, and I was intrigued by the cover and the heft of A Short Introduction to Anneliese (2025), and when I flipped thru it, it was full of pictures and charts and written music,

and I’ve been on this thing lately trying to figure out what constitutes a 21st-Century-Novel:

. . . some of you dead-ass write like the 20th Century never happened, that’s how I feel when I see someone euphorically laud Dubliners (1914) like yeah the ending to

The Dead is really cute, but. . .

R U SERIOUS?

(there’s nothing to learn from Dubliners that hasn’t been osmosed into even the most basic, proficient novels du jour),

Joyce wrote 2 novels that you can still learn from (well, one, time & dispersion has rendered Useless, learning, if not pleasure-wise): U & FW. . .

One thing I am SURE is part of the 21st-Century-Novel is EXACTLY what James Elkins is doing:

VISUAL VARIETY.

If I flip thru your book and it looks to Mein Eye like a Henry James novel but it was written in our magnificent quarter-old century, forgive me bruh, but I’m not spending my hard-earned bucks on it.

Anyway that’s a topic for a different day. . .

THRU A LITTLE GOOGLING around, I found out that Anneliese was the second installment of a five-volume jumbo-novel called Five Strange Languages of which Weak in Comparison to Dreams is the first. . .

(though, in reality, Dreams is volume 3, and Anneliese is volume 2.)

4. BACK TO THE SHOW! (THE SHOW IN QUESTION BEING ANIMALS IN DISTRESS//WHAT IS THIS: SEA WORLD??)

THIS BOOK IS ALSO full of charts and threaded-thru fictional science papers,

NOT science-fiction. . . they are papers of real science written by our author, read by Samuel.

And if reading that sounds boring to you,

U R DUMB, BRUH, u don’t know what u r missing.

(I will read ANY paper on ANY topic by a scientist who doesn’t really exist, but a real scientist. . . I think I’ll pass. . . )

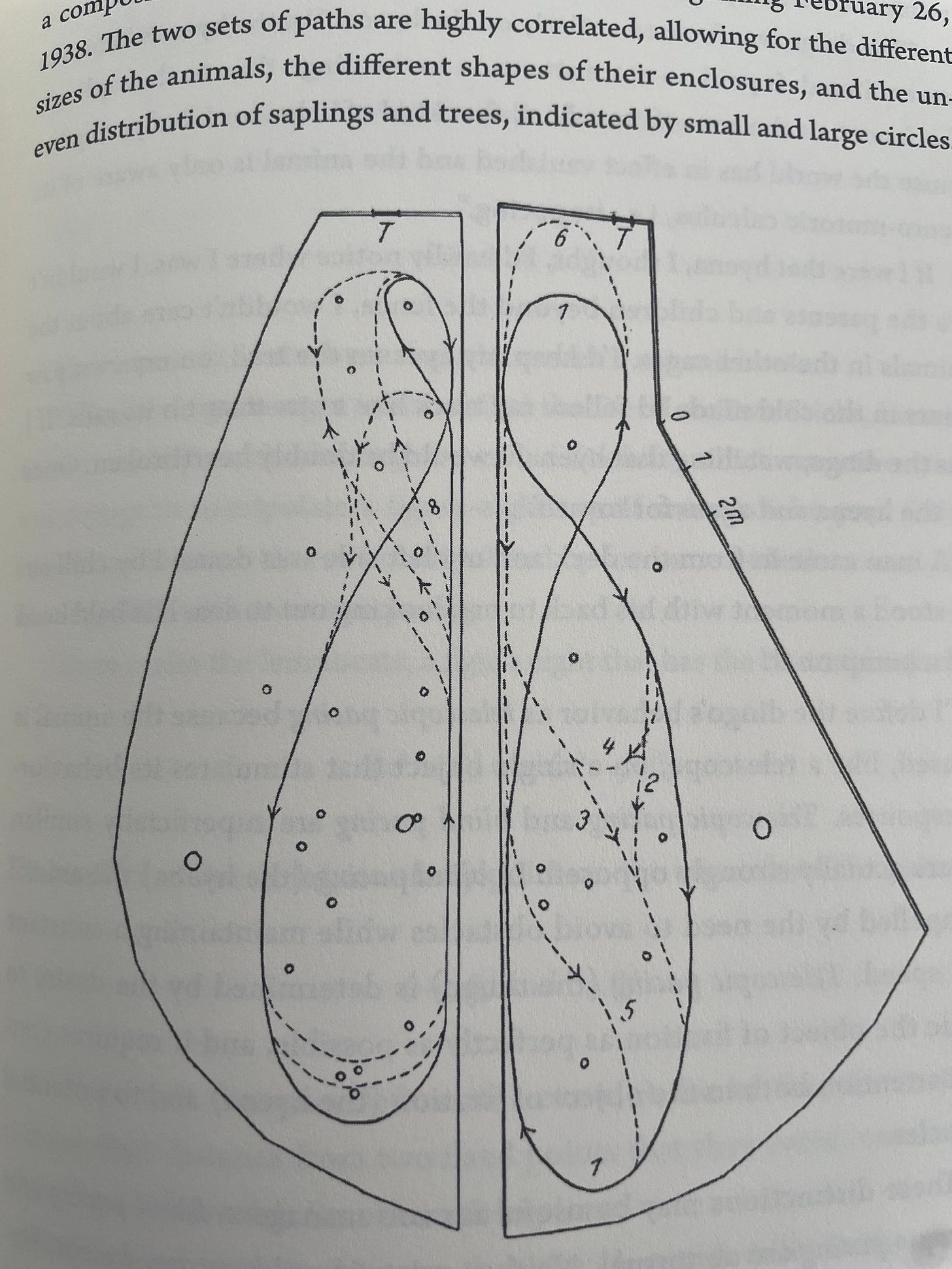

MONIKA WOODAPPLE observed a hyena and a dingo from the roof of an enclosure at the Berlin Zoo,

In the autumn and winter of 1937, I spent a total of 210 hours of observation time in the Berlin Zoo, gathering the data for this study. My field materials included a folding chair, plans of the animals’ cages, pencils and notebook, stopwatch, pocket watch, hand and foot warmers, and a pair of opera glasses. In inclement weather I covered myself in a felt blanket. . . I remained motionless for many hours at a time. . . Children pointed at me, but I did not move or answer.

What we learn is that distressed animals move in repetitive patterns.

The hyenas and the dingo were moving in traceable figure 8s dictated by the confines of their cage;

what Samuel starts to realize is that he is a distressed animal too:

PREDICTABLE, CONFINED, REPETITIVE. . .

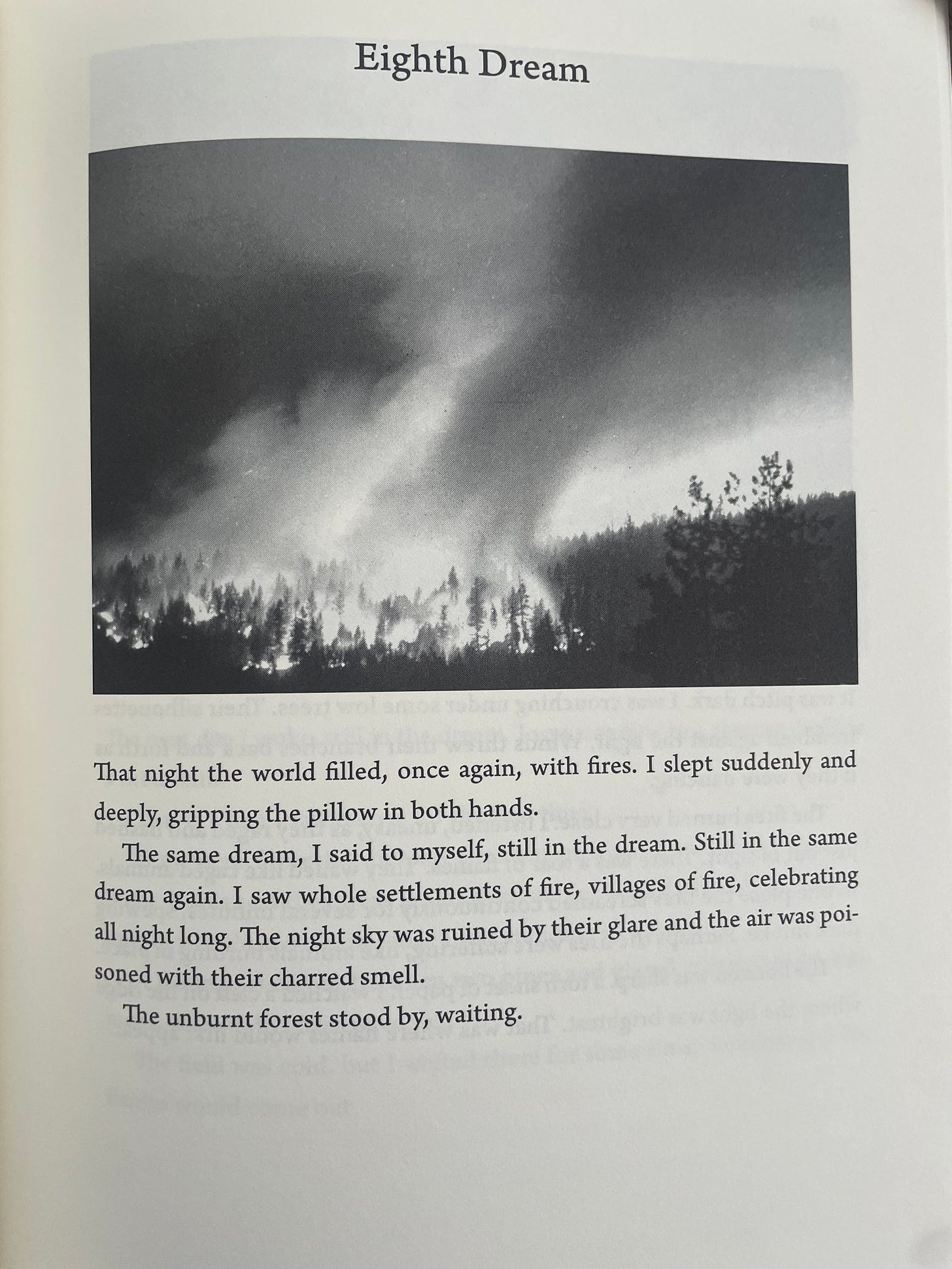

A FIRE STARTS to creep up on Samuel in his dreams.

He is in a burning forest he doesn’t recognize.

The fire is burning thru his reason, his stable personhood.

Samuel is an amoeba specialist, right? I think he’s sunk by his imaginative capacities.

Having respected such small life forms, when he’s faced with a distressed, depressed large mammal, how can he reckon with their imprisonment?

With the hell of their lives?

Further extrapolating, how can he deal with the hell of his own life if he is one of these freeless, imprisoned mammals?

Samuel sees too much,

An image of a constellation of colored daddy longlegs hung in my mind. They might have been pretty from a distance, but if you looked too closely, your heaven would resolve into colored bellies with shivering legs and lots of tiny silver eyes. That tent must have been claustrophobic, with all those daddy longlegs so close above their heads. Same thing with the heavens, I thought. They’re only sublime because we have weak eyes. Close up they are a mess: black holes, lethal radiation leaks, dust and rocks flying all over the place, those frightening voids between galaxies.

SOME OF THE ANIMALS are in really rough shape.

Here is a chimp at Zoo Knoxville who is trapped in a painful, unstoppable loop of repetitive behavior,

I saw Owole’s life stretching out ahead of her. The minute I’d been watching would become an hour, then a day. Then months, years. What is a minute, if every minute is the same as every other? I felt a weird elasticity of time. As if the monkey had decided she could not longer stand the whining freeway, the miserable patch of woods, the forlorn warehouses at the end of the zoo. She was protesting her intolerable existence by trying to stop time. If she did the same thing over and over, each time identically, then time would have to stop. She was refusing to let time pass. She was pretending she lived in a single spontaneous moment. But she was also torturing herself by extending time, making each second more painful than the last by making each second exactly equal to the last.

And here is a poor iguana, Lucy, who has had a hysterectomy,

On top of the rock under a garish orange light, was a large iguana, flopped out, legs hanging down. Its eyes were closed. It appeared dead. Its skin was dry past repair cracked and stained like an old concrete building.

And yet, everybody at the zoo insists the iguana is happy; all the animals are happy, even though they’re all doped up on psychiatric meds.

This is an anaesthetized world.

It’s hard to tell if the condition of the animals is getting grimmer and grimmer, or if Samuel’s perception is just getting sharper as his sense of self deteriorates and he starts seeing himself as these animals, in prison, doing whatever he can not to feel the reality of the world.

EVENTUALLY SAMUEL GETS FIRED because he acts crazy as fuck on these zoo visits.

Here’s what he tells his guides at the Salt Lake Zoo,

—Your tiger still has hope, but god knows why, after what you’ve been doing. Next time it comes out and sees the cliff raised up even higher, it will probably collapse in despair. You’ll have to give it Haldol, too, and then it’ll jump around. That will be great for the visitors. It’ll seem frightening and vibrant like a tiger should. In fact, now that I think of it, why not give all your animals Haldol? Ellie will dance the jig. Visitors will think she’s having a great life. Your tarantulas will scurry all over the place. Children will squeal with delight. . . Antipsychotics all around! Your zoo can be a dance club. Horror show psychotic animal dance club. Every animal jumping and running like your demented devil. The zoo will be full of howling and shrieking and barking and roaring and chirping and grunging.

I made a selection of the appropriate noises.

Despite the Inferno all around, this book is certainly much funnier than Dante.

5. AFTER THE COLLAPSE

SAMUEL DRIVES AND DRIVES and drives, gets lost, has a final dream, and the main narrative ends with pictures of animals (finally).

But the book’s formal brilliance isn’t over.

We get 100 pages of Notes now, written by Samuel Enner, now that he’s 90+, mostly alone in his house, accompanied by droves & droves of sheet music.

He’s commenting on the book Samuel Enner wrote that he found in a dusty old manuscript in his attic; but that Samuel is a different person,

When Samuel Enner wrote this book, he was trying to understand what happened that year. I think mainly he wanted to know what he was supposed to do with the fact that each week his life was becoming stranger, more strangulated.

All he has now is his piano & his music; his daughter, Fina, visits with her husband, and they’re going to put him in a nursing home.

This is not something we usually ever get, in a novel, the postscript to the most intense experience in someone’s life, decades later.

He’s lonely, but he’s fine. Time passes,

I no longer feel the pressure of that year. Samuel was crushed between his asphyxiated days and his airless nights. He was trapped. His days were filled with random sights and sounds, like preludes. His nights were a single landscape, unfurling ahead of him like the unspooling themes of a fugue, overlapping, intertwining, braiding into a forest. The iron stares of the animals clamped down from above, and the teeth of his dreams pierced him from below. I feel sorry for him, if that makes sense, but it was long ago, and he was not me.

But Samuel doesn’t deal with reason anymore;

he’s removed himself from quantifiable, traceable, imaginative experience: it’s all music now, diffuse feeling.

I loved this part. There’s so many riffs on composers & art-making.

There’s invented composers too (surely more than I realized), like Asgar Gaarn, who composes 24 preludes & fugues dedicated to the deceased and he sends them to the dedicatee with letters,

Dear Mr. Gyorgy Ligeti, Gaarn writes, it is very sad to me you have died. I wonder if you ever got my letters. I wrote you three times. I asked why you only wrote eight preludes and fugues. Eight is a very unusual number. Twelve is common, as you know. I myself prefer twenty-four, the number Bach has given us. I wonder if Bach has asked you that yet now that you are in heaven. I suspect he will. It’s very strange. I am sure he is curious. Why would anyone write eight? Please say hello to Bach for me. Yours, Asger.

Gaarn’s letters were cracking me up.

TIME PASSES. DEATH LOOMS,

Little Sam has gone away, much father than Samuel, and he took his entire world with him. Now I’ve left Samuel behind as well. He’s evaporated, gone like the knotted concentration of the little boy who drew these animals. This is how memory disperses, how generations can pass within a single lifetime.

Proust wrote an optimistic book about memory, how it flowers in the imagination until your past swirls around you, pearlescent and welcoming. He was young, still woven into the cocoon of his childhood. If he had lived long enough, he would have wondered at the middle-aged man who spent so long cultivating his past. Memories do not wait forever. If too much time passes, they walk away. All that’s left are books that no longer speak, like headstones scoured blank by the rain.

I MUST INSIST TO YOU how much fun I had reading this book.

It is truly like nothing else being published right now.

I read it in 3 delightful days.

And it’s clear to me, 2 volumes in, that Five Strange Languages is a major, major work.

If you care about what imaginative literature is capable of in the 21st-Century, ESPECIALLY, in the United States, you MUST read this book:

there are still boundaries to push, there are still original yarns to be spun.

READ IT FUCKERS. . . OR WITHER.

Illuminating

Adding this to my list, excited to check it out!